Scholar Plays Key Role in Collaborative Studies

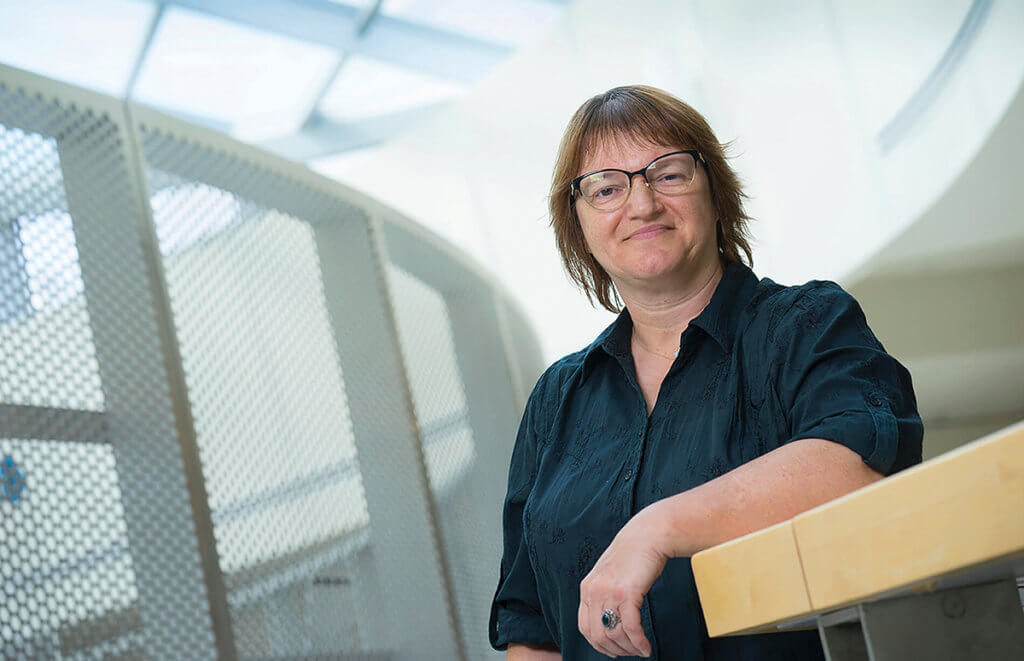

Although scientists know that the solution to preventing breast cancer won’t come easily, a team of researchers, including Dr. Sophie Lelièvre, professor of cancer pharmacology in Purdue Veterinary Medicine’s Basic Medical Sciences Department, has announced the recent discovery of one of the puzzle pieces to cancer prevention. The team of scholars at Purdue University and the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM)/Institut de Cancérologie de L’Ouest (ICO) in Nantes, France has been investigating whether herbicides can cause breast cancer.

The Purdue Center for Cancer Research (PCCR), working with ICO, the Cancer Center for Western France, as part of a memorandum of agreement with the Purdue-led International Breast Cancer and Nutrition (IBCN) initiative, discovered that glyphosate, the primary ingredient in widespread herbicides, can lead to mammary cancer when combined with another risk factor. The work was published in Frontiers in Genetics.

“This is a major result and nobody has ever shown this before,” said Dr. Lelièvre, co-leader of IBCN. “Showing that glyphosate can trigger tumor growth, when combined with another frequently observed risk, is an important missing link when it comes to determining what causes cancer.”

Scientists exposed noncancerous human mammary epithelial cells to glyphosate in vitro over a course of 21 days. The cells were then placed in mice to assess tumor formation. Although cells exposed to glyphosate alone did not induce tumor growth, cancerous tumors did develop after glyphosate was combined with molecules that were linked to oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is a chemical reaction that occurs as the result of aging, diet, alcohol consumption, smoking or other stressors, and it alters the organization and integrity of the genome of the breast, aiding cancer development.

“What was particularly alarming about the tumor growth was that it wasn’t the usual type of breast cancer we see in older women,” Dr. Lelièvre said. “It was the more aggressive form found in younger women, also known as luminal B cancer.”

Glyphosate has been the subject of widespread scientific debate when it comes to cancer research. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency said in a 2017 risk assessment that the herbicide was likely not carcinogenic. However, in 2015, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer said glyphosate was “probably carcinogenic.” Research that was published in 2017 also associated glyphosate with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Another key discovery researchers made was the ability to identify the pathway, at the epigenetic level (i.e., the chemical marks on DNA and proteins that control gene expression), used by glyphosate to endanger breast cells. Dr. Lelièvre and the lead scientist on the project from ICO, Gwenola Bougras-Cartron, hope this evidence will enable researchers to both detect and reverse the risk for breast cancer when associated with this combination of risk factors.

“There is a huge gap in the research that is targeted at understanding why cancer develops,” Dr. Lelièvre said. “This discovery is novel, primarily because until now, there hasn’t been any scientific evidence to show that a second factor when associated with common pollutants would be sufficient for cancer to develop. It’s very difficult to determine what causes breast cancer, but this is a critical step forward in the right direction so we can start working toward prevention as we have outlined in the international collaborative work of IBCN.”

Cancer incidence continues to rise globally, with breast cancer being the most common type, according to Cancer.gov. Dr. Lelièvre said those facts alone continue to fuel the motivation for her research with the hope of eventually finding a way to prevent cancer before it even starts. “There has been a heavy focus on research for both treatment and detection, but prevention just isn’t as prevalent,” Dr. Lelièvre said. “If we can find a way to mitigate the risks, we can have hope for fewer cases.” The work was funded by the National League against Cancer in France (Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer).

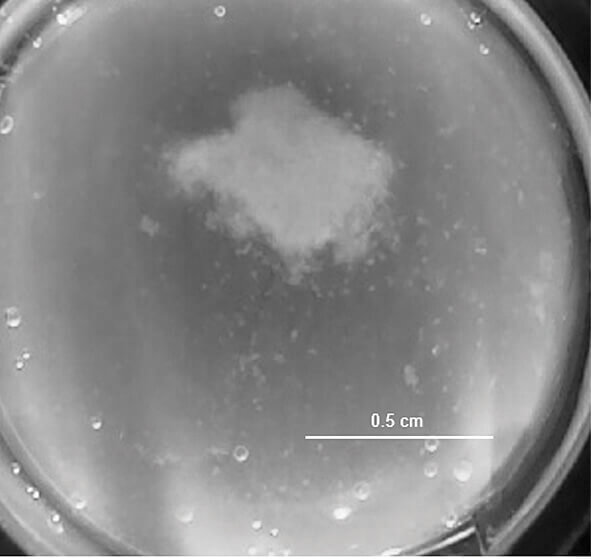

Dr. Lelièvre is a proponent of state-of-the-art cell culture models that replicate different phases of cancer development for research and she has been working with a team of researchers at Purdue to develop a device, with funding from the Congressionally-Directed Medical Research Program/Breast Cancer Research Program, which will help identify risk factors and underlying mechanisms that cause breast cancer. She is also working with researchers to create tumor models in 10 days that are much closer in size to the ones found in the human body to help test new therapies and screen for drug sensitivity. “This is a first for cancer research,” Dr. Lelièvre explained. “For the first time we have created tumor models in the laboratory called macrotumors that are 0.5 to 1 centimeter in width and 1.5 centimeters in height. This is much closer to the size of small tumors detectable in patients, and remains viable for days, even weeks, enabling therapeutic drug testing.”

Dr. Lelièvre is co-leader of the Drug Discovery and Molecular Sensing Program of the PCCR. She explained that in addition to a comparable size of tumors, their in vitro models are valuable because they maintain the structure of the tumors as found in the body, so they can decide which microenvironmental characteristics of cancer to recapitulate. “This is critical for testing drug delivery and finding medicines that readily target the cancerous cells in tumors and help save lives. It’s another step forward in the pursuit of precision medicine.”

Dr. Lelièvre added that the novel tumor design was made possible because Purdue cancer researchers from across disciplines come together with support from the PCCR and the 3D Cell Culture Core (3D3C) Facility of the Birck Nanotechnology Center in Purdue’s Discovery Park. “The 3D3C is really a unique facility that you won’t find anywhere else in the world,” said Dr. Lelièvre, who initiated 3D3C in 2015 and serves as the scientific director for the facility. “We are able to bring together engineers and biologists to create models based on 3D cell culture, including tumor models, which help move research forward to the people who need it most.”

The technology is being patented through the Purdue Research Foundation Office of Technology Commercialization. The scientists are looking for partners to test and commercialize their technology.