A Purdue University research team led by Dr. Riyi Shi, professor in Purdue Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Basic Medical Sciences and the Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, has identified a molecule that appears to play an important role in the development of Parkinson’s disease. The discovery could lead to therapies, potentially including drugs currently on the market, as well as potentially facilitating earlier diagnosis and prevention of the neurological disorder.

Parkinson’s disease is a debilitating disease that affects millions of people around the world. Dr. Shi and his colleagues identified a compound that accumulates in Parkinson’s disease-affected brain tissue. The compound, acrolein, is a toxic, foul-smelling byproduct of burning fat (the brain uses fat for fuel) and is normally eliminated from the body. But the research team found that the substance can promote the build-up of a protein called alpha-synuclein. When this protein accumulates in a region of the brain called the substantia nigra, it destroys the cell membranes and key machineries of neurons, killing these brain cells.

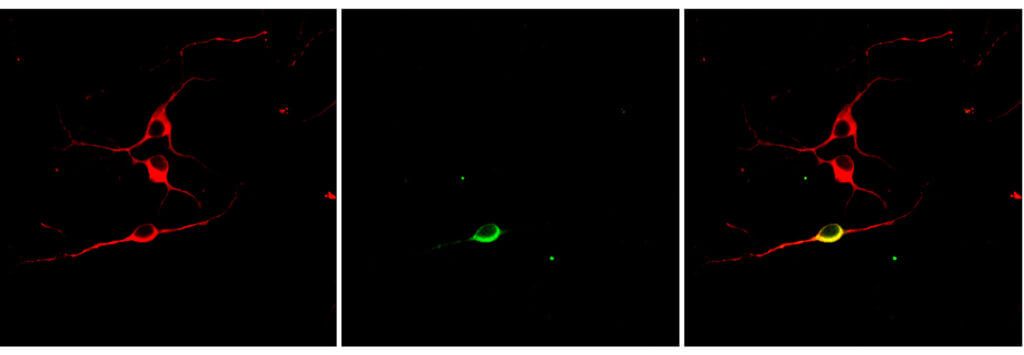

These images of a brain cell culture show dopamine neurons similar to those that die in the brains of Parkinson’s disease patients. The image on the left shows a cell culture stained to reveal a marker present in all neurons (red) or only in dopamine neurons (green). The right panel shows a merged image in which a dopamine neuron is stained yellow. (Purdue University photo/Aswathy Chandran)

Dr. Shi explained that when this cell death becomes extensive enough, the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease become evident. “Acrolein is a novel therapeutic target, so this is the first time it’s been shown in an animal model that if you lower the acrolein level you can actually slow the progression of the disease,” Shi said. “This is very exciting. We’ve been working on this for more than 10 years.”

Dr. Jean-Christophe (Chris) Rochet, professor in the Department of Medicinal Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology in the College of Pharmacy, and a co-investigator on the study, adds a cautionary note. “In decades of research, we’ve found many ways to cure Parkinson’s disease in pre-clinical animal studies, and yet we still don’t have a disease therapy that stops the underlying neurodegeneration in human patients,” he said. “But this discovery gets us further down the drug-discovery pipeline, and it’s possible that a drug therapy could be developed based on this information.”

Dr. Rochet said that in experiments using both animal models and cell cultures, the role of acrolein was confirmed. “We’ve shown that acrolein isn’t just serving as a bystander in Parkinson’s disease. It’s playing a direct role in the death of neurons.” The research is published in the April issue of the scientific journal Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience.

Parkinson’s disease is a chronic, irreversible disease, and it is the leading cause of disability in people over the age of 60 — affecting nearly one million people in the United States and 7-10 million worldwide. It is the 14th leading cause of death in the United States and the second leading neurological cause of death, behind Alzheimer’s disease. The disease can occur either early or late in life, and its symptoms — tremors, slow movements, difficulty walking — get progressively worse over time. The risk of developing the disease is thought to be determined by both genetic and environmental factors.

With such visible symptoms, the public often becomes aware when a well-known person has the disease. This list of people affected by Parkinson’s disease includes actor Michael J. Fox, singer Neil Diamond, the Rev. Jesse Jackson, singer Linda Ronstadt and former U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno. If further studies show that acrolein plays a similar role in Parkinson disease in humans, it may be possible to detect and forestall the disease in its early stages.

A second finding from the research is that the scientists were able to mitigate and even reverse the effects of Parkinson’s disease in both animal models and cell cultures using hydralazine, a drug used to treat high blood pressure and congestive heart failure. “Luckily, this is a compound that can bind to the acrolein and remove it from the body,” Dr. Shi said. “It’s a drug already approved for use in humans, so we know there is no toxicity issue.”

Dr. Rochet cautions that the drug may not ultimately be the best therapy for Parkinson’s. “Because it is used to lower blood pressure, it might not be the best choice for Parkinson’s patients. Or, we may find there is a therapeutic window, a lower dose, that could work without leading to unwanted side-effects,” he said. “Regardless, this drug serves as a proof of principle for us to find other drugs that work as a scavenger for acrolein.”

“It is for this very reason”, Dr. Shi adds, “that we are actively searching for additional drugs that can either more efficiently lower acrolein, or do so with fewer side-effects. Actually, we have already identified multiple candidates that can lower acrolein with similar or greater effectiveness, but without lowering blood pressure, providing further hope that such a strategy could be successful in Parkinson’s patients.”

Dr. Shi said that early detection of Parkinson’s disease is critical — symptoms often aren’t noticeable until approximately 50 percent of the neural cells in the substantia nigra have died. “The key is to have a biomarker for acrolein accumulation that can be detected easily, such as using urine or blood,” he said. “Fortunately, we have already established such a test using urine or blood samples. The goal is that in the near future we can detect this toxin years before the onset of symptoms and initiate therapy to push back the disease. We might be able to delay the onset of this disease indefinitely.”

In 2017, Dr. Rochet was part of an international team that found, using epidemiological data from Norway, that a common asthma medicine, salbutamol (also known as albuterol) could reduce the risk of Parkinson’s disease by half. This research was selected as one of the top 10 drug discoveries for 2017 by the publication Technology Networks. “Evidence suggests that salbutamol acts by a different mechanism than hydralazine – that is, by reducing alpha-synuclein accumulation – and thus perhaps salbutamol and an acrolein-scavenging drug could be used together to achieve an even greater therapeutic effect,” Dr. Rochet said.

Drs. Shi and Rochet are both faculty members of the Purdue Institute for Integrative Neuroscience and the Purdue Institute for Drug Discovery. Both centers are located in Purdue’s interdisciplinary research facility, Discovery Park.

This work was supported by the Indiana State Department of Health grant number 204200 and by funding from the National Institutes of Health, grant numbers NS073636 and NS049221. This research also was funded in part by the Stark Neurosciences Research Institute, Eli Lilly and Co., the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, and the Branfman Family Foundation.

Dr. Shi also is the co-founder of Neuro Vigor, a startup company with business interests of developing effective therapies for CNS neurodegenerative diseases and trauma. Previously, Dr. Shi was one of three scientists who developed Ampyra, the first and only FDA-approved drug to help multiple sclerosis patients improve their motor skills.