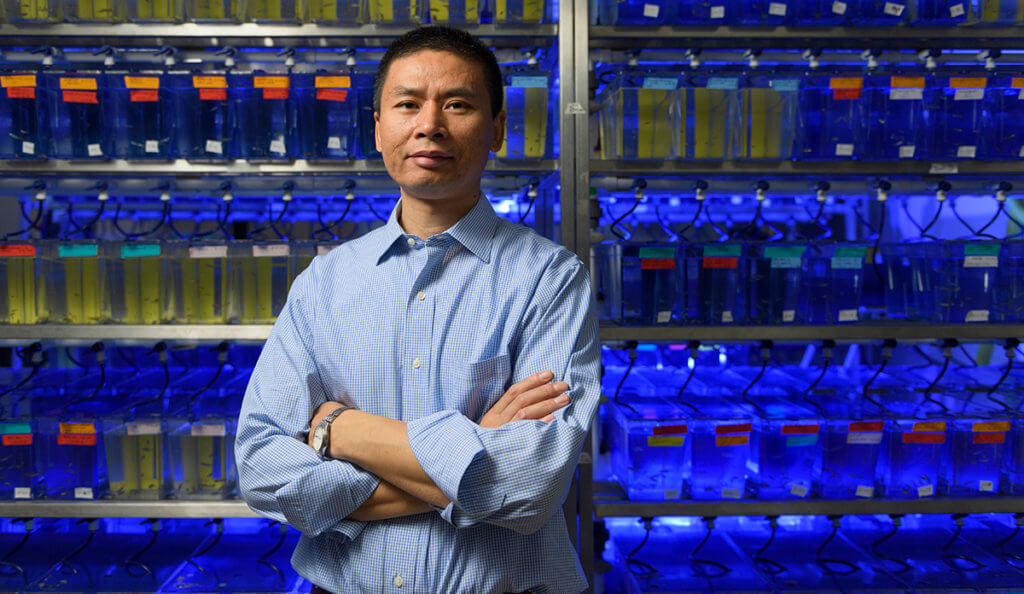

Purdue Veterinary Medicine had a record-breaking year securing $12 million in research funding. Dr. GuangJun Zhang conducts research involving zebrafish, which is a model for studying human cancers.

Purdue Veterinary Medicine had a record-breaking year securing $12 million in research funding. Dr. GuangJun Zhang conducts research involving zebrafish, which is a model for studying human cancers.

Purdue has a great deal to celebrate in 2019. As the University hails 150 years of “Giant Leaps,” the College of Veterinary Medicine marks its 60th Anniversary as a national standard-bearer for veterinary education and animal health care.

Purdue’s No. 1-ranked Veterinary Teaching Hospital — the veritable Mayo Clinic of the veterinary world — has attracted patients from 42 states and Canada. But that’s just part of its 60-year story.

Many of the same faculty responsible for educating future veterinarians and providing top-ranked health care to animals also are drawing in record amounts of funding for research — research that in most cases promises to benefit humans as well as animals. In the 2017-2018 fiscal year, the College’s research garnered more than $12 million — an all-time high.

How did it happen? Groundbreaking science showing strong potential to benefit both animals and humans has been key. It has attracted large investments from agencies such as the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Double-duty Research

Casual observers might assume that PVM research is exclusively for or about animals. Dr. Willie Reed, dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine, is eager to dispel that notion.

“I want people to understand the impact we have and the role that our veterinary research plays in human health as well as in animal health,” Dean Reed says. “A lot of our faculty use animal models of human disease. We do breast cancer research and work on the impact of animals on children with autism. Many people might not think about a veterinary college doing that.”

Not only is the scope of the research broader than presumed, but there is a lot of it — hence the record-high funding.

“Our faculty, including recent new hires, are doing a terrific job at submitting grants and getting them funded. We also have a strategic plan for our College, and one of the goals is to focus more on the research enterprise,” Dean Reed says.

That strategic focus is directed at five areas of research emphasis:

- Animal Welfare Science and Human-Animal Bond

- Cancer

- Infectious Diseases and Immunology

- Musculoskeletal Biology and Orthopedics

- Neuroscience

Dr. Harm HogenEsch, associate dean for research and professor of immunopathology, leads PVM’s flourishing research efforts. He says he is delighted by the share of the research funding increase that can be attributed to new faculty hired within the past five years.

“It takes time for faculty to submit proposals and get their research off the ground,” Dr. HogenEsch says. “I see these new faculty being successful and it’s very gratifying.”

Dr. HogenEsch adds that he, too, is inspired by the dual benefits for humans and animals in much of the research: “A prime example is the work in antimicrobial research and in new treatments and drugs to overcome antibiotic resistance. We are making significant contributions in that area and many others.”

What follows are several examples of the College’s trendsetting research.

Breakthroughs for You and Your Animals

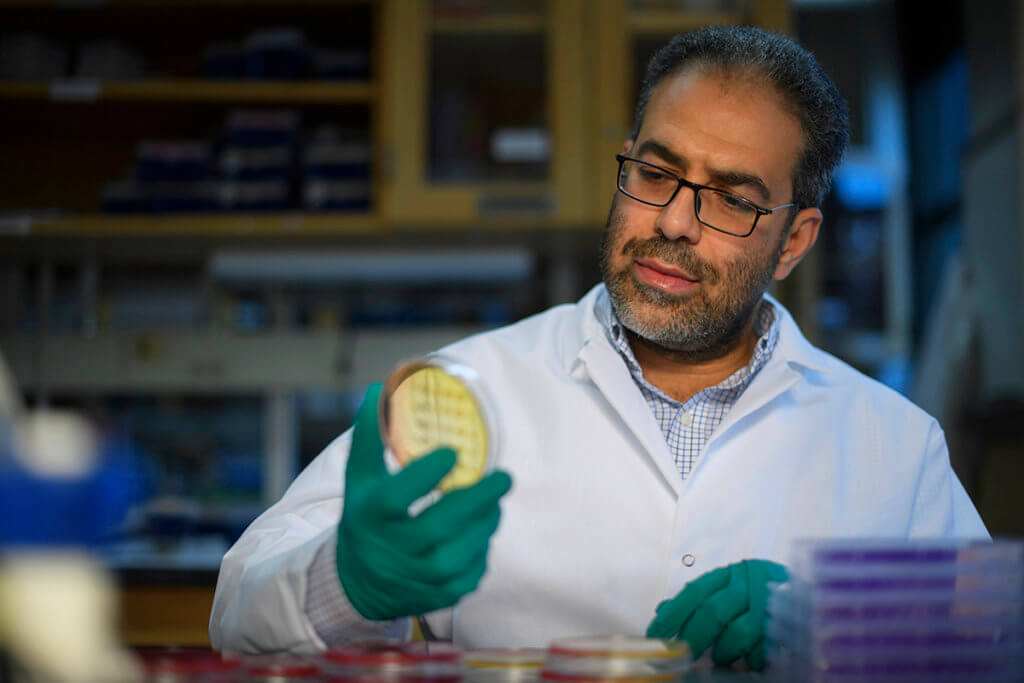

Dr. Mohamed Seleem // Infectious Diseases & Immunology

“If only we had known sooner, we could have treated it right away.” A quote like that, often heard after a preventable death, motivates Dr. Mohamed Seleem. The professor of microbiology in the Department of Comparative Pathobiology is very excited about tests that he and his 14-member team are doing on an early-detection method for infections.

“It currently takes over a day to identify a micro-organism,” Dr. Seleem says. Depending on when the infection begins, a day spent waiting for test results could mean the difference between survival or death.

“We are able to identify the infection with only a single bacterium or fungus in blood within 10 to 20 minutes with the method we’re testing,” Dr. Seleem says. He hopes that the promising technology could be approved for use in humans in five years.

Since 2017, the NIH has supported Dr. Seleem’s research aimed at repurposing existing drugs in the fight against MRSA and Clostridium difficile, known as C. diff, a life-threatening diarrhea that infects nearly 500,000 people a year in the United States and kills 15,000 annually.

Dr. Seleem’s team also is working on several other antimicrobial drugs to meet the urgent need to fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The World Health Organization has compared the rising number of drug-resistant infections to a “slow-motion tsunami” that could kill millions and undermine the global economy.

A Cancer-fighting Win-win

Dr. Deborah Knapp // Cancer

You will look far and wide to find researchers more knowledgeable, passionate, or with a greater sense of urgency about their work than Dr. Deborah Knapp. As the Dolores L. McCall Professor of Comparative Oncology and director of the Purdue Comparative Oncology Program — the oldest program of its kind in the nation — Dr. Knapp treats dogs, helps their families, and makes discoveries that help people.

Dr. Knapp is a strong advocate for cancer researchers to do more of the kind of research she does — cancer studies that involve animal models like dogs with specific types of cancer that more closely resemble cancer in humans than traditional laboratory animals such as mice, rabbits, and rats. “It’s becoming painfully obvious that better animal models of cancer are needed for cancer treatment because nine out of every 10 human cancer trials fail when relying only on traditional laboratory research and studies with lab animals,” Dr. Knapp says. “When we test drugs in dogs that have naturally occurring cancer, the results are expected to be much more predictive of results in people.”

Dr. Knapp is a strong advocate for cancer researchers to do more of the kind of research she does — cancer studies that involve animal models like dogs with specific types of cancer that more closely resemble cancer in humans than traditional laboratory animals such as mice, rabbits, and rats. “It’s becoming painfully obvious that better animal models of cancer are needed for cancer treatment because nine out of every 10 human cancer trials fail when relying only on traditional laboratory research and studies with lab animals,” Dr. Knapp says. “When we test drugs in dogs that have naturally occurring cancer, the results are expected to be much more predictive of results in people.”

Dr. Knapp says she is in a very exciting time with her research into bladder cancer in dogs. “We are tapping into the expertise of members of the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research as well as scientists at other institutions including the NIH, Duke University, Johns Hopkins University, and Vanderbilt University,” she says. “Our work is covering prevention, early detection, and treatment. Everything we’ve done for over 30 years has contributed to where we are now.”

Dr. Knapp says tests on dogs using the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug piroxicam have shown enough promise to warrant human clinical trials: “If you give piroxicam by itself, 20 percent of dogs have their bladder tumors shrink dramatically, while 55 percent to 60 percent of dogs’ tumors will shrink a little, or stop growing,” she says.

Even more intriguing, Dr. Knapp says, are results from three trials showing remission rates doubling in dogs taking piroxicam in combination with a chemotherapy drug. “I have no reason to think that this wouldn’t happen in people,” she says.

Cancer Research That’s Letting up on the Accelerator

Dr. Marxa Figueiredo // Cancer

The very real prospect of healing damage from rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with scientific methodology that also can slow the growth of cancerous tumors, dominates Dr. Marxa Figueiredo’s research. The associate professor of basic medical sciences is developing new therapeutics that stimulate the body’s immune system to help prevent tumor growth and/or heal the bone damage that RA causes.

Dr. Figueiredo’s lab is studying a new gene therapy to treat RA that would deliver a targeted form of a specific protein (interleukin-27). “It acts as a kind of damage-seeking immune bullet,” Dr. Figueiredo says. “We use targeting to send the protein to the areas that need repair.”

Dr. Figueiredo’s lab is studying a new gene therapy to treat RA that would deliver a targeted form of a specific protein (interleukin-27). “It acts as a kind of damage-seeking immune bullet,” Dr. Figueiredo says. “We use targeting to send the protein to the areas that need repair.”

Dr. Figueiredo says her long-term goal is to heal RA damage rather than manage its symptoms: “Current therapies can effectively control the inflammation for this disease, but they can’t reverse the bone loss. New lines of therapies are emerging that can target the immune component of the disease, but they are very expensive and still cannot promote bone or cartilage repair.”

Dr. Figueiredo’s work also is showing promise against aggressive forms of cancer in the pancreas, prostate, colon, liver, and breast. Her team has developed a drug that interferes with a membrane protein that promotes the growth of cancer cells and tumors.

“We are trying to take cancer’s foot off the accelerator by targeting this receptor,” Dr. Figueiredo explains.

Understanding Cancer’s Moment of Mutation

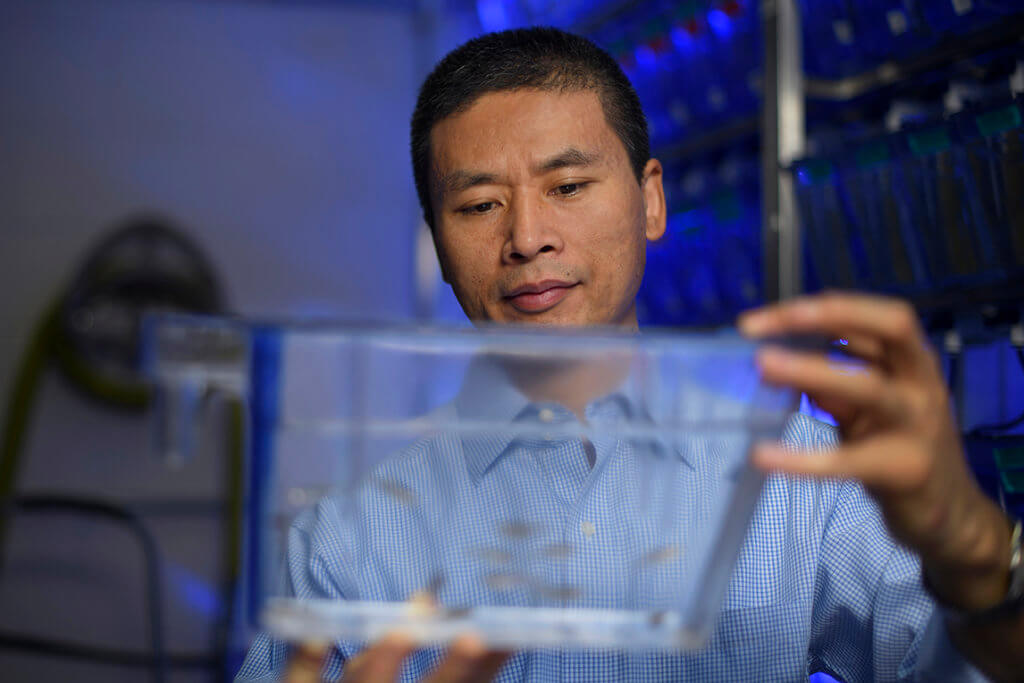

Dr. GuangJun Zhang // Cancer

Research to explain cancer’s genesis in the body is happening in Dr. GuangJun Zhang’s lab, where the deadly disease’s complex and largely mysterious genetic mutations are being investigated. Dr. Zhang is the College of Veterinary Medicine’s John T. and Winifred M. Hayward Associate Professor of Genetic Research, Genetic Epidemiology, and Comparative Medicine, in the Department of Comparative Pathobiology.

“The critical genes that contribute to tumorigenesis are called ‘driver genes,’ while genes that do not contribute are called ‘passenger genes,’” Dr. Zhang explains. “One of the goals of current cancer research is to identify cancer driver genes, so we can use them as therapeutic targets, as well as diagnosis- and prognosis-makers.”

“The critical genes that contribute to tumorigenesis are called ‘driver genes,’ while genes that do not contribute are called ‘passenger genes,’” Dr. Zhang explains. “One of the goals of current cancer research is to identify cancer driver genes, so we can use them as therapeutic targets, as well as diagnosis- and prognosis-makers.”

To achieve this goal, Dr. Zhang employs a comparative genetic approach using zebrafish – fresh water fish usually found in an aquatic pet store. Dr. Zhang’s lab looks like an aquatic center, with an intricate system of towering aquarium tanks filled with zebrafish. “The zebrafish is not only a pet fish, but also one of the prominent vertebrate model organisms for current biomedical research,” Dr. Zhang says. The zebrafish is widely used in the field of developmental biology due to its large number of progeny, early transparent embryos, and tractable genetics as well as the ease with which the fish can be maintained. Recently, they also have begun to play a role in human disease research areas including cancers. Mutations of many genes that are homologous (comparable) to human cancer genes have been found to also lead to cancers in zebrafish, demonstrating that the zebrafish is a great model for studying human cancers.

With many cutting-edge genetic tools such as CRISPR and Tol2 transposon, Dr. Zhang says his team is now in the process of identifying key genetic players in the transition of a normal cell to a cancerous cell.

Puppy Mills No More: Raising Standards for Commercial Dog Breeders

Dr. Candace Croney // Animal Welfare Science & Human-Animal Bond

The term “puppy mill” has strong connotations, none of them good. With common news stories about abused or neglected dogs in large kennels, commercial breeding kennels have gotten a bad reputation, being lumped-in as puppy mills.

Enter the research team led by Dr. Candace Croney, who holds a joint appointment as professor of animal behavior and well-being in the College of Veterinary Medicine and professor of animal sciences in the College of Agriculture. Their work helps to distinguish commercial breeders from true puppy mills while also helping to raise the standard of care across breeding kennels regardless of how they are categorized.

Enter the research team led by Dr. Candace Croney, who holds a joint appointment as professor of animal behavior and well-being in the College of Veterinary Medicine and professor of animal sciences in the College of Agriculture. Their work helps to distinguish commercial breeders from true puppy mills while also helping to raise the standard of care across breeding kennels regardless of how they are categorized.

With nearly $2 million from the Stanton Foundation, Dr. Croney and her research team are the first to go on-site to commercial breeding kennels to study dog welfare. Dr. Croney is quick to point out that there are good stories about kennels, but they don’t get our attention. “I’ve found that there are a lot more people than the Internet would have us believe who actually want to do well by their dogs,” Dr. Croney says. “People have been so busy judging these kennel owners that they don’t stop to help.”

Dr. Croney says she works to help breeders whose operations are doing less than they can because of a lack of knowledge about what to do differently. “Our goal is to promote a culture change in commercial dog breeding that supports high welfare standards and sustainable pet ownership.”

To that end, Dr. Croney’s team gathers new scientific knowledge on dog behavior, welfare, and management in commercial kennels, and provides it to breeders who use her expertise in adopting research-based dog-welfare policies and best practices.

Dogs as PTSD Sufferers’ Best Friends

Dr. Maggie O’Haire // Animal Welfare Science & Human-Animal Bond

In the first study of its kind, a physiological marker was used to measure how service dogs benefit victims of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Dr. Maggie O’Haire, associate professor of human-animal interaction, looked at veterans’ saliva levels of cortisol, a hormone produced when the body responds to stress. Veterans collected samples themselves after waking up in the morning, and a second time about 30 minutes later. Extensive previous studies in non-PTSD, healthy adults show that an increase in cortisol when waking up is typical.

In the first study of its kind, a physiological marker was used to measure how service dogs benefit victims of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Dr. Maggie O’Haire, associate professor of human-animal interaction, looked at veterans’ saliva levels of cortisol, a hormone produced when the body responds to stress. Veterans collected samples themselves after waking up in the morning, and a second time about 30 minutes later. Extensive previous studies in non-PTSD, healthy adults show that an increase in cortisol when waking up is typical.

“This innovative study applies rigorous research methodology to an area that has historically been characterized by a reliance on anecdotal accounts and intuition rather than evidence-based science,” Dr. O’Haire says. The research found that veterans with a service dog in the home produced more cortisol in the mornings than those without a dog — a pattern closer to the cortisol profile expected in people without PTSD.

“These findings present exciting initial data regarding the physiological response to living with a service dog,” Dr. O’Haire says, adding that the findings need to be assessed in context. “The study did not establish a direct correlation, on an individual level, between cortisol levels and levels of PTSD symptoms, and further study is needed.”

Dr. O’Haire is now focused on a large-scale NIH clinical trial comparing veterans with and without service dogs over an extended period of time. “Our research team will be able to look at morning cortisol levels both before and after getting a service dog to see how these physiological effects manifest over time,” Dr. O’Haire says. Additionally, the study will record information from high-tech devices like data-transmitting collars for dogs and data-tracking wristbands for veterans. “The longitudinal nature of this clinical trial should bring about a better understanding of the interrelationships between physiological and behavioral processes, PTSD symptoms, and service dogs,” Dr. O’Haire explains.

A Promising Future

The current surge in PVM research portends more scientific advances in all five of the College’s areas of research emphasis as faculty-led research teams make even greater contributions to animal and human health and well-being in the future, Dean Reed says.

One example involves utilization of high tech tools for data gathering in traditional areas of veterinary medicine. “We’ve already been using various devices to measure animal behavior,” Dean Reed says. “We also will be able to collect data with devices that pets wear to track heart rates and activity and exercise rates, as well as monitor compliance with medicine administration.” In the case of animal agriculture, new technology makes it possible to monitor a herd of 10,000 cattle with ear tags that measure body temperature.

“As exciting as these developments are, we have the potential to more broadly impact animal and human health and well-being through big data-driven approaches to biomedical problems,” Dean Reed says. “Technologies such as systems biology, including genomics and proteomics, and GIS data, combined with bioinformatics and machine learning hold great promise for combatting disease and promoting animal and human health. Veterinary medicine has a key role to play in advancing these areas of research, as well as in addressing global health challenges such as antimicrobial resistance, food security, and protection from biological and environmental hazards.”

Purdue Veterinary Medicine is well positioned, Dean Reed says, to make great contributions in these areas with its team of innovative research scientists. “This is an amazing time to be a veterinary medical scholar. The opportunities before us to positively impact animal and human health and well-being are unprecedented.”