Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory Stands in the Gap to Protect Purdue

It was a daunting problem – unprecedented in modern times – that Purdue University and the College of Veterinary Medicine faced just over a year ago. The scourge of the COVID-19 pandemic that spread around the globe had become entrenched, shutting down all but essential services and closing campuses nationwide. Purdue students had been sent home in the middle of the spring semester of 2020, as faculty and staff put forth a herculean effort to convert instruction to distance learning formats. As spring turned into summer, Purdue and College of Veterinary Medicine leaders looking ahead to the 2020-2021 academic year sought to address the unparalleled challenge of determining how to return to in-person instruction for the fall semester while protecting the health and safety of students, faculty, and staff.

A huge part of the answer to that dilemma involved COVID-19 testing – in massive amounts. The testing had to be fast and accurate, and available to anyone on campus experiencing symptoms, as well as people selected randomly for surveillance testing. Across Indiana, testing demand already had put a strain on the system that was in place for evaluating human COVID-19 samples. Once in-person classes started again (pre-testing was required of all students before the school year began), where could the University turn to find a resource capable of high throughput testing that would be accurate and reliable to protect the campus population?

The answer was right on campus. It just was camouflaged by the word “animal” in the name. The rest of the name, though, revealed the nature of this resource and its capability to meet the challenge. The Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (ADDL), a service of the Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine, had the right equipment as well as highly trained staff with the expertise and experience needed to process tens of thousands of human COVID-19 samples using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, considered the gold standard for diagnosing the illness. The only catch was that the laboratory needed to obtain special certification to do the same test on human samples that it routinely did on thousands of animal diagnostic samples.

The certification, known as Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certification, is required for laboratories performing diagnostic testing of human samples. Dr. Kenitra Hendrix, ADDL director and clinical associate professor of veterinary diagnostic microbiology, said the process of obtaining the certification was readily accomplished largely due to the ADDL’s established quality control system. At that point, the stage was set for the ADDL to answer the call for high volume, rapid, and reliable COVID-19 testing to help ensure the safety and health of the campus population when in-person classes resumed last August.

Hindsight, more than a year later, reveals the wisdom of that plan. Dr. Hendrix said as of May of this year, the lab had completed 198,475 COVID-19 tests, all with a typical turnaround time of one day or less. “We performed 32,833 tests in March of this year alone,” Dr. Hendrix recalled. “Our team worked seven days per week since last fall. Our laboratory technicians have been amazing. They pushed through all during the year, to meet the University’s need to receive continuous test results, including on Saturdays and Sundays.”

Dr. Rebecca Wilkes, associate professor of molecular diagnostics and head of the ADDL’s Molecular and Virology sections, oversaw the day-to-day testing work. “I am so impressed with our technicians,” Dr. Wilkes said. “They have gone above and beyond, and worked really hard to provide the University with the needed results, most of the time on the same day as the samples were received.”

Even Purdue’s success athletically depended on the ADDL’s work. Dr. Hendrix noted that the lab arranged for extra shifts to provide Purdue Athletics with athletes’ test results before game times in accordance with Big10 regulations.

Recognizing the importance of performing PCR tests in protecting the broader community, the ADDL also provided testing services to outside entities including a local hospital and a small college, as capacity allowed.

And all of the COVID-19 testing came on top of the ADDL’s already significant workflow, which involves testing several hundred animal samples per week for diseases ranging from avian flu to foot and mouth disease (FMD).

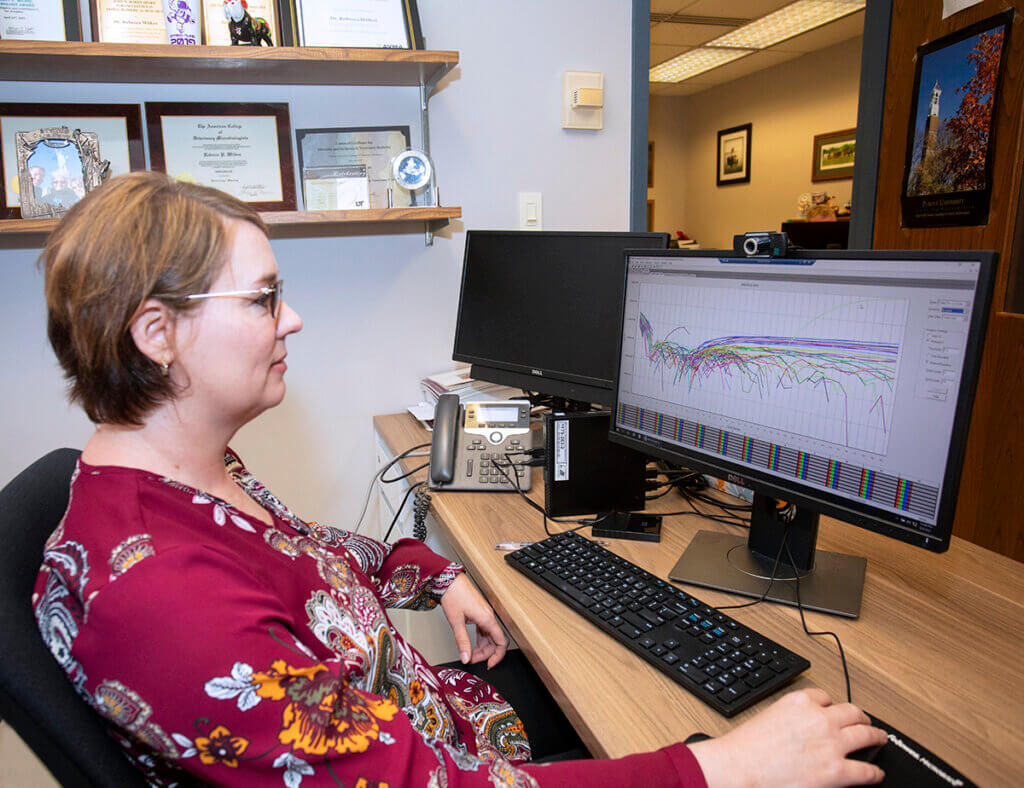

“Our capabilities not only involve having the necessary equipment, but also vast expertise,” explained Dr. Hendrix. “Dr. Wilkes understands the ins and outs of PCR tests to the point that she could troubleshoot issues with the data generated from the software that’s required for human COVID-19 PCR test interpretation. She recognized when circumstances required a more detailed review of results, to ensure that they were accurate – and that positives were indeed positive. She manually reviewed all results to be certain the automated readings were right, and made corrections as necessary to protect the integrity of the results.”

The testing saga took another turn when 2020 gave way to the new year and variants of concern emerged, including the B117 variant, initially called the UK variant. “That particular variant had a characteristic that we could detect with our PCR test,” Dr. Wilkes said. “So we were able to see when that variant surfaced in people on campus.” As word spread about additional variants of concern that could not be detected as part of the PCR test, the ADDL partnered with another lab on campus, the Carpi Lab, which had the ability to do the sequencing needed to identify those variants. Directed by Dr. Giovanna Carpi, assistant professor in the Department of Biological Sciences and a member of Purdue’s Institute of Inflammation, Immunology and Infectious Disease, the Carpi Lab already had been sequencing malaria samples and quickly pivoted to sequence COVID-19 samples.

“When we found samples that were positive for COVID-19, we would send them to the Carpi Lab so they could be subjected to the sequencing that would reveal if they contained one of the variants of concern,” Dr. Wilkes explained. “Working together, we found several of the variants of concern, including the ones popularly referred to by the regions where they were identified, and since renamed by the World Health Organization as the Beta, Gamma and Delta variants, along with B117, now called the Alpha variant.” In so doing, the labs, along with the Protect Purdue Health Center, have been able to track the novel coronavirus in the Purdue community and throughout the state of Indiana, providing information that helps ensure that city, state, and university leaders have the best and most accurate, up-to-date information possible.

“When challenges like this arise, Purdue steps in,” said Purdue Veterinary Medicine Dean Willie Reed, who co-chaired the Safe Campus Task Force and serves as head of the university’s Vaccine Allocation Task Force. “The combination of scientific and engineering excellence makes us stand out from the crowd. We have STEM expertise, including a world-class veterinary medical school, biomedical researchers, and more. People from all areas of the University have stepped up as we knew they would, using their expertise and willingness to immediately apply their knowledge to this worldwide challenge.”

Dr. Hendrix said Dr. Wilkes’ expertise and experience has played a huge role in the University’s successful testing program. “PCR testing is complex and there’s no substitute for having someone with Dr. Wilkes’ extraordinary level of know-how overseeing the PCR testing of COVID-19 samples to ensure that the findings are accurate, dependable, and timely. I can’t say enough about the phenomenal work Dr. Wilkes and her team accomplished to help ensure that the University had the data it needed to protect Purdue.”

Dr. Hendrix also lauds the work done by Dr. Carpi and her lab. “While we have sequencing capability at the ADDL, our workload had reached a point where we knew it was best not to do sequencing on positive COVID-19 samples ourselves,” Dr. Hendrix said. “Dr. Carpi’s team had the sequencing protocol in place and the pipeline to analyze the vast amount of data produced by the sequencing.” Dr. Carpi explained that in addition to her work for Purdue, the Indiana State Department of Health even sent samples directly to her for genome sequencing instead of to the CDC, since her lab could turn results around faster.

It all added up to a winning strategy. A Protect Purdue Summary Report published by the University found that, by taking a data- and insight-driven approach to testing, the University was able to be more efficient, effective, and responsive in helping ensure the safety of its students, faculty, staff, and most vulnerable members of the University community. “The result was an uninterrupted level of learning, research, and student-faculty engagement during this challenging year, where not a single case of COVID-19 was traced to a Purdue classroom and only one case tied to a research laboratory,” the report said.

Looking ahead, Dr. Hendrix said the ADDL is working toward being able to also conduct sequencing of positive COVID-19 samples to identify variants of concern. “Because the ADDL is CLIA certified, sequencing data generated in our laboratory may be used by medical professionals for making medical decisions,” Dr. Hendrix said.

As a footnote, the ADDL was in good company nationally as it pivoted to test COVID-19 samples. Of 37 laboratories that are members of the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN), a total of 25, including Purdue’s, performed testing of human COVID-19 samples. The role played by these laboratories in the national effort to combat the pandemic reflects the importance of the concept of One Health – the collaborative and transdisciplinary approach to achieving optimal health outcomes, recognizing the interconnectedness of people, animals, and their shared environment.