Though educated in America’s heartland at Purdue University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, two Boilermaker veterinarians are at the leading edge of scientific discovery in aquatic medicine. Both successfully pursued careers as veterinarians in marine science and hold key positions at well-known enterprises focused on marine mammal health. Their scholarship was spotlighted in an article in the February edition of The Scientist magazine.

The article celebrated a breakthrough in aquatic biology research regarding treatment of infections in fish. The story covers the history of the problem, including preliminary contributions made by the two Purdue alumni — Dr. Andrew Stamper (PU DVM ’93) and Dr. Michael Murray (PU DVM ’77) — over the last several years. Antifungal and antiparasitic drugs were decaying in quarantine tanks, making the treatment of infections more difficult. The article discussed research that finally proved prior suspicions about microbial organisms causing these disappearing drugs.

Future research will seek to find more practical solutions for balancing the microbiomes of aquariums so that sick fish can be treated efficiently and effectively. Dr. Stamper’s and Dr. Murray’s contributions built a foundation for continued research, and Dr. Murray has plans for further investigations of his own.

About Dr. Andrew Stamper

Dr. Andrew (Andy) Stamper is the conservation science manager and veterinarian for Disney Conservation. Raised in the Midwest, Dr. Stamper spent his summers in high school traveling to Maine and working for Project Puffin on offshore islands where he enhanced his passion for marine life. As he pursued his interests, Dr. Stamper studied marine sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and then returned to the Midwest to enroll in the Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine, where, as a student, he represented Purdue in studies of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska’s Prince William Sound, examining the effects of the oil on marine river otters. He earned his DVM degree in 1993 and, for the past 21 years, has been with Disney’s Animal, Science, and Environment team, focusing on marine animal and ecosystem health.

About Dr. Michael Murray

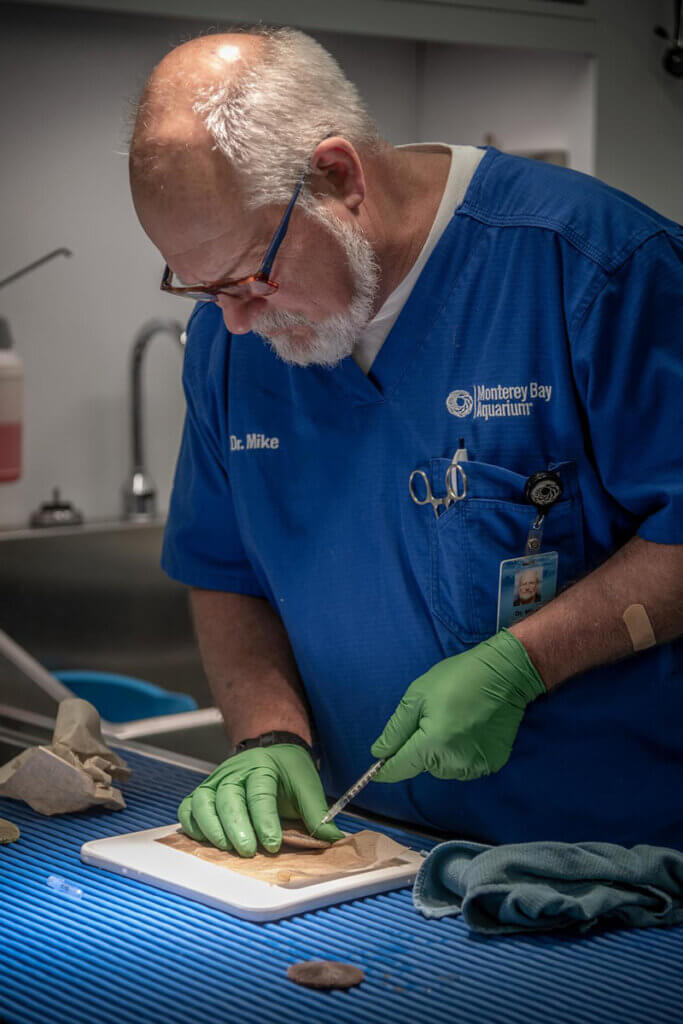

Dr. Michael Murray (often referred to as just “Dr. Mike”) earned his Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree from Purdue University in 1977 and is currently the Jane Dunaway Director of Veterinary Services at the Monterrey Bay Aquarium, as well as a research associate at the University of California, Santa Cruz. In addition, he serves on the Accreditation Commission of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), which honored him as Accreditation Inspector of the Year in 2011. Dr. Mike is a leading authority on sea otter conservation efforts from California to the Russian Far East. He provides routine healthcare for animals in the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s living collection, from sea otters to shorebirds to giant Pacific octopus and also is deeply engaged in the exhibit and field research activities of the Aquarium. He was honored by his peers in 2002 as Exotic Veterinarian of the Year.

About The Scientist Article

The Mystery

It comes as no surprise to any seasoned aquarist that microbes and bacteria are abundant in tank ecosystems. As quoted in the article, Dr. Stamper commented that, “…if you actually look at the bioload in an aquatic system, the bacteria either equals or outdoes the fish.” Of course, some bacteria can benefit the health of the tank and its inhabitants, while others can cause serious harm. The harmful types of bacteria must be studied to reduce and prevent harm for fish and other aquatic life. Starting in 2015, Dr. Stamper noticed that formalin, which is used as an antifungal and antiparasitic drug in fish medicine, was disappearing from treatment tanks faster than it could cure afflicted fish. The concentration of the drug was decreasing exponentially, rather than linearly, suggesting that the cause was biotic (caused by living organisms).

In 2016, Dr. Stamper hypothesized in a paper that bacteria may be the cause. He suspected that the connection had not been investigated previously because much aquarist research focused on the benefits of certain bacteria which metabolized ammonia in tanks. The thought that microbes might be able to influence drug concentrations to such a large extent “…wasn’t an idea that was floating around in our circles at the time,” Dr. Stamper noted. He intended to further this investigation, but sequencing technology to explore the details of a tank’s microbiome was not readily available. Curious to pin down the cause for this mystery, though, Dr. Stamper continued to build a body of supporting evidence, ruling out other causes as best he could in publications that documented similar losses of the antiparasitic drug, Praziquantel. In the case of that drug, too, Dr. Stamper proposed bacteria as a possible explanation after noting that Praziquantel did not degrade in tanks that had been sterilized.

Meanwhile, Dr. Murray noticed similar problems with the antiparasitic drug, Chloroquine, also used as a human antimalarial drug, which was degrading during the treatment of tropical fish with parasitic infections. Like Dr. Stamper, Dr. Murray began conducting his own small-scale experiments to rule out other abiotic causes. “We had a number of meetings trying to figure out why it was happening,” Dr. Murray said in the article. After these experiments, Dr. Murray and his team continued to work under the assumption that bacterial degradation was taking place because they couldn’t figure out another explanation for it. Validating this assumption, though, would prove difficult.

The Research

Staff at the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago had found the same Chloroquine degradation patterns. Dr. Bill Van Bonn, Shedd’s vice president of animal health, knew of the work by Drs. Murray and Stamper suggesting bacterial causes. He then partnered with Dr. Erica Hartmann, environmental microbiologist at Northwestern University. The experiments they did together found nearly 800 types of bacteria in tank samples. About 20, all members of the same phyla, seemed to be connected to the degradation of Chloroquine. Further examination showed that these microbes were involved in the breakdown of nitrogen, using it as a source of food.

The Answer

The article also quoted a microbial ecologist from the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Dr. Pia Moisander, who, though not involved in the work, said she was not surprised by the phyla responsible for the degradation of these drugs. They are quite common in tank samples. Dr. Moisander believes that specific species within this phyla group could be identified using fluorescent labeling on different isotopes to make it easier to track the drugs and how they are broken down. She also noted that it could be worthwhile investing time and money into finding the solutions to questions that are yet unanswered even after the work at Shedd Aquarium.

For now, aquarists have a few ways to manage the degradation of important drugs in their tanks. Temporary tanks or smaller tanks may be sterilized with hydrogen peroxide before being used to treat infected fish. Because this is not feasible for larger, permanent tanks, the pipes can be flooded with fresh water and scraped clean every few months to kill the microbials responsible for this effect.

The Future

The Scientist article adds, “Species-level resolution might help explain why degradation happens in only some tanks, or only sometimes, and resolve some remaining mysteries.” One such mystery, pointed out by Dr. Murray, is that Chloroquine degrades faster in less crowded tanks. There may be a connection between high ammonia levels in crowded tanks and the persistence of drug-eating microbials. Dr. Murray began testing the outcomes when fish-excreted ammonia is not filtered out as drugs are introduced – the hypothesis being that bacteria with access to alternative food may not consume the drugs as quickly. Meanwhile, Shedd Aquarium is searching for bacteria species that may be able to compete with the varieties that are consuming drugs. There are many possible avenues for this research to continue, leading to better care for ill fish. While several of these possibilities are being explored now, there is a lot left to understand about the phenomenon.