If you haven’t heard of an Allosaurus before, expect the name of this Jurassic-era predator to become much more familiar in the years to come, as a planned future exhibit at the acclaimed Children’s Museum of Indianapolis takes shape, with some help that was provided by the Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine. That help enabled the museum’s paleontology team to obtain needed high tech CT (computed tomography) scans of a prehistoric fossil courtesy of the Purdue University Veterinary Hospital’s Diagnostic Imaging team.

The scanning happened over the spring and summer and resulted in one of the most unusual scenes to ever unfold in the hospital’s facilities. But understanding those events requires a bit of background, dating back to a stunning find by the paleontology team during the summer of 2020 at The Jurassic Mile® — the museum’s fossil-rich dig site in Wyoming. They stumbled upon a previously undiscovered set of bones in a completely different layer of rock than the stratum that had yielded different dinosaur fossils found before.

As explained on the museum’s website, after clearing away the debris, the team was stunned to find a stone block containing an articulated Allosaurus fossil – meaning the bones were connected in the exact order and position that they would have been in when the animal was still alive. It was an incredibly rare find, and over the succeeding years the Allosaurus fossil was brought to Indianapolis and the work of preparing for the future Allosaurus exhibit began in the paleontology lab.

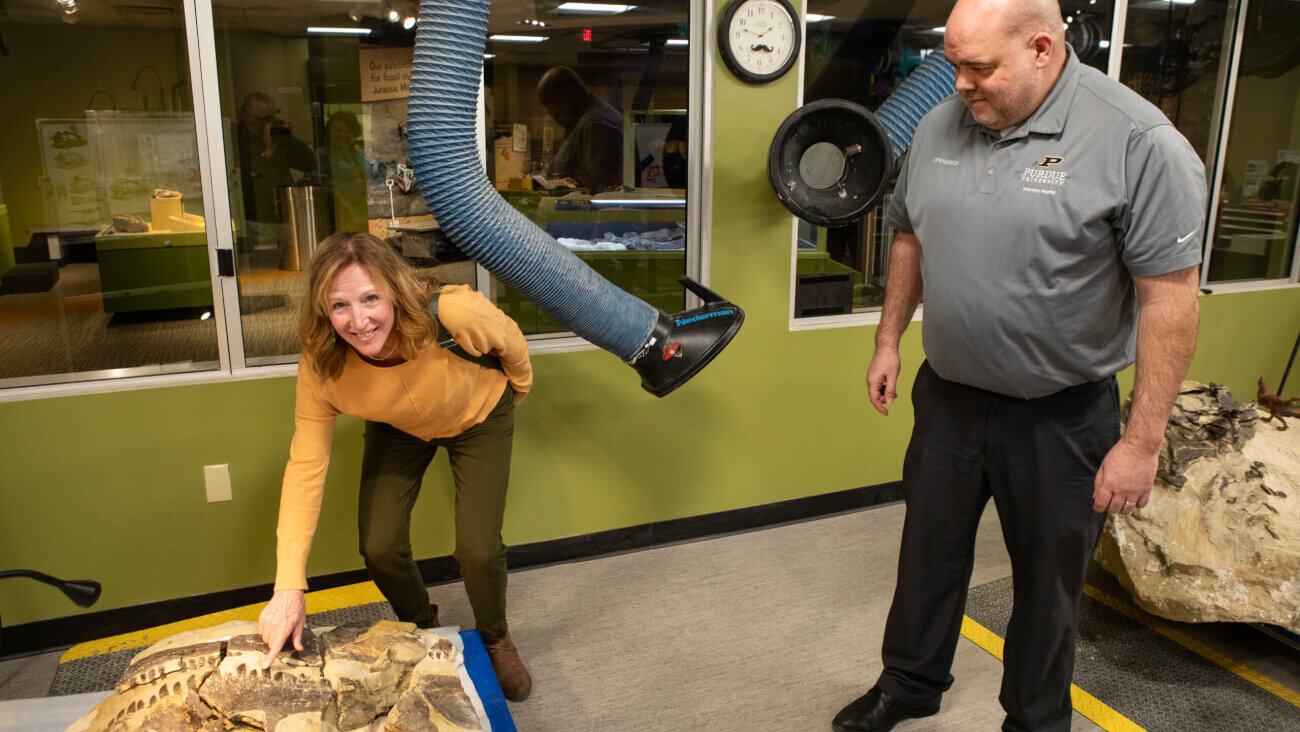

Fast-forward to the summer of 2025. That’s when portions of the fossil arrived at the Purdue University campus in West Lafayette, where they could be scanned by the advanced CT imaging equipment in the David and Bonnie Brunner Equine Hospital. On a typical summer morning, a very atypical scene unfolded as the museum paleontology group teamed up with the Veterinary Hospital Diagnostic Imaging crew to bring the fossil through the Equine Hospital’s large breezeway to the CT room.

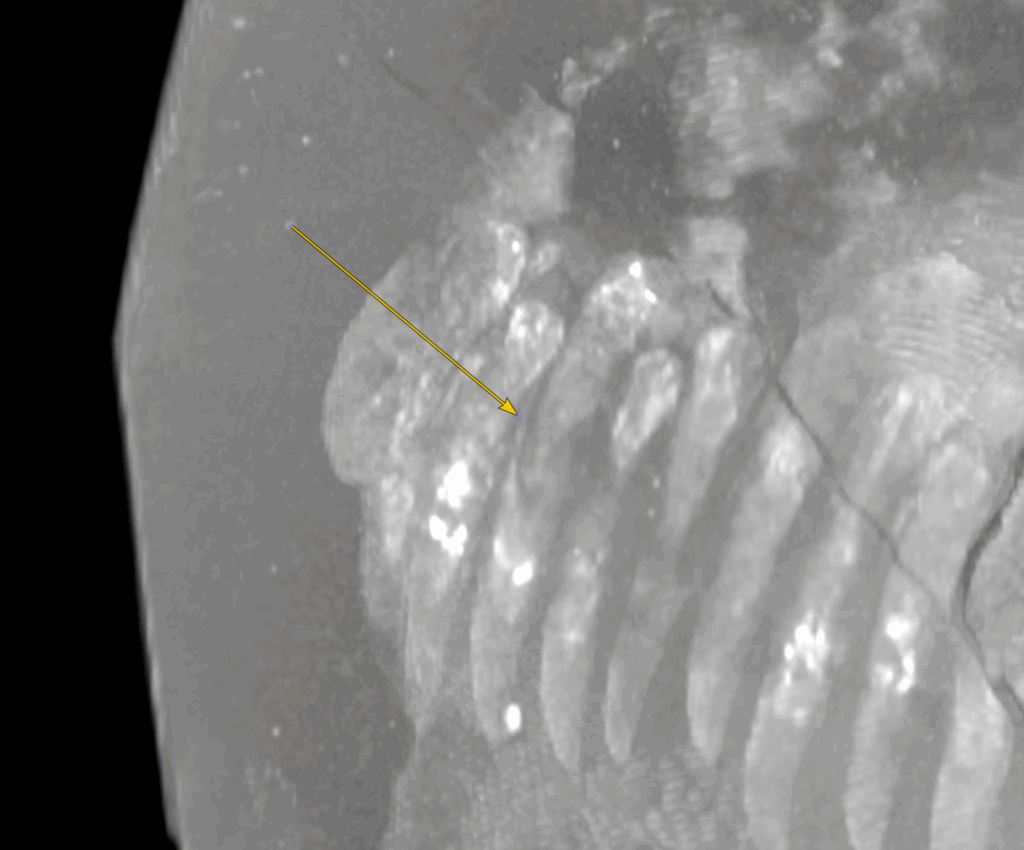

“The Allosaurus fossil is encased in very hard, iron-rich sandstone,” explained Joseph Frederickson, the museum’s lead paleontologist and Natural Sciences manager. “This rock, originally deposited by a river, helped bury and protect the animal for millions of years. Because the burial happened so quickly, we believe there is fossilized skin preserved on the right side of the specimen. This means we can’t simply remove all the surrounding rock. Instead, we use CT scans to see inside the matrix, helping us guide the preparation process and digitally reconstruct the dinosaur’s anatomy without physically disturbing the fossil.”

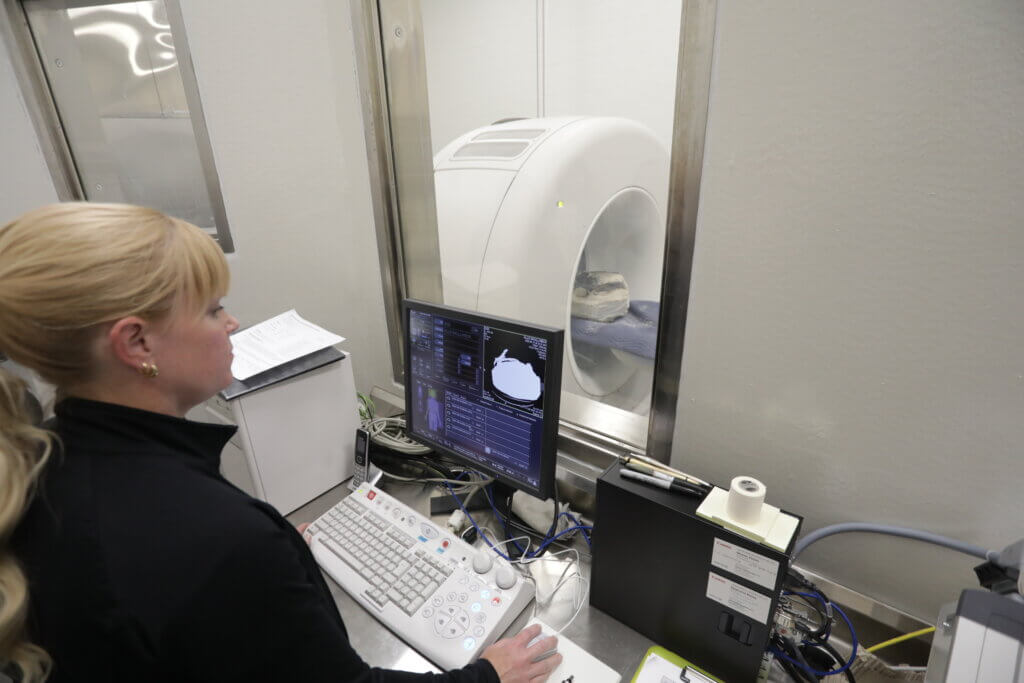

The museum reached out to the Purdue University Veterinary Hospital for help and the collaboration was born. “It was very cool,” said Donna Tudor, Diagnostic Imaging veterinary technologist supervisor, as she described the experience of planning for and conducting the scans of the fossil specimens. “It was a great opportunity to collaborate with the museum and support their public outreach.”

Also directly involved in the scanning was Christy DeYoung, Diagnostic Imaging veterinary technologist. “When Donna first told me about the opportunity, I was beyond excited! Working at a university we already see so many interesting cases but scanning a dinosaur fossil isn’t something I ever expected to be part of my job, and I was thrilled that we would be working together with the wonderful staff at the Children’s Museum to do so,” DeYoung shared.

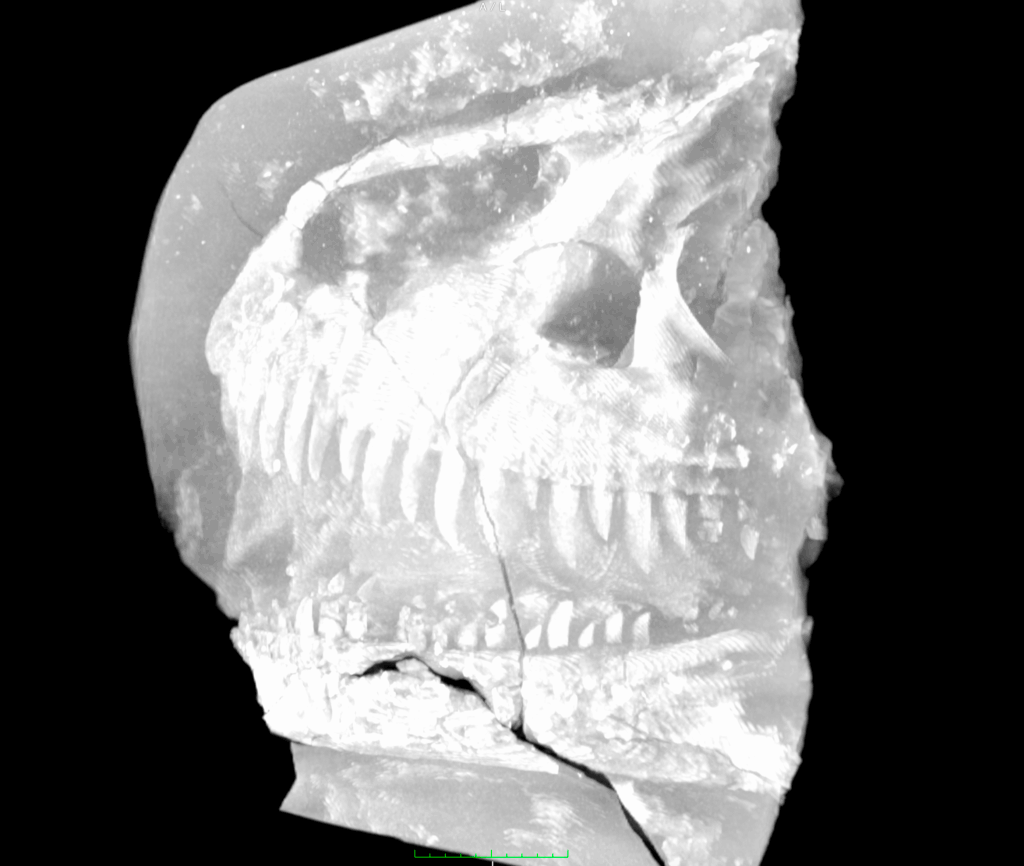

Frederickson said that though conducting CT scans on fossils has become increasingly common in paleontology, this is the first time the museum’s team has used CT scans to assist directly in uncovering a fossil during preparation. “CT machines aren’t designed to image solid rock, so we needed to use higher-powered scans than those typically used for living organisms,” Frederickson noted. “Fortunately, this doesn’t harm the fossil and is considered a safe practice. One side of the skull scanned beautifully, revealing fine details, including replacement teeth still inside the jaw.”

Earlier in the spring of 2025, Dr. Carrie Fulkerson, clinical associate professor of diagnostic imaging, and senior diagnostic imaging resident, Dr. Jack Jarvis, helped the team determine which of the Purdue University CT scanners would create the best images. “The Children’s Museum team brought a small rock with a few fossils for us to test,” Dr. Fulkerson said. The images created on the Qualibra CT in the David and Bonnie Brunner Equine Hospital allowed for the best optimization of the bone density within the rock.

“This was a great opportunity for collaboration and to provide our support to such a rare discovery,” Dr. Fulkerson commented. “It also provided our team an opportunity to think outside our day-to-day routines and see something completely different.”

For Tudor, it was a fascinating first-time experience. “I was really expecting to not see much,” she said. “Rock is so dense but the bones were denser – so we were able to distinguish between the two.”

Frederickson said the thicker back portion of the skull required additional preparation before they could obtain scans capable of penetrating the dense rock. For DeYoung, the experience was especially meaningful. “To be able to see and touch an actual fossil was such a rare opportunity and I’m so happy we were able to collaborate with he Children’s Museum and provide this service to them. I’m beyond grateful and proud to think that our CT scans will aid in a future exhibit and hopefully provide crucial information to the paleontology team in their research moving forward.”

Tudor actually visited the museum with Joey Woodyard, director of hospital operations, earlier in the year in order to plan for the scanning process. “The paleontology team was great showing us around their facilities, and then providing us with specific parameters we could use on the CT scanner to enhance the images.” She also noted that she was glad the paleontology team members were the ones who handled the specimens. “The fossils are very heavy and quite fragile. I was afraid to help move them for fear of dropping a very important part of our history!”

The scans were conducted over the course of a couple of paleontology team visits to the hospital, during which the two teams had a chance to get to know each other. “I have immense gratitude for the diagnostic imaging team and their willingness to dedicate time and expertise to this project,” Frederickson said. “Combining our knowledge of fossils and geology with their understanding of imaging technology gave us our first clear look at this 150-million-year-old animal.”

Frederickson adds, “This Allosaurus is scientifically invaluable, and there’s still much to learn about it. The scans taken at Purdue have already proven essential, allowing us to visualize the bones and surrounding rock early in the process. This insight helps us make informed decisions during preparation, preserving more of the fossil and revealing details we might otherwise have missed.”

There’s still much work to be done and Frederickson said they anticipate that the museum’s future Allosaurus exhibit will take another five years to complete. But there’s no need to wait to get a peek at what it will include. “Anyone interested in seeing the Allosaurus is welcome to visit the Paleo Lab at The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis,” Frederickson said. “We’re currently preparing the skull, neck, and tail, and the work is visible to all visitors in the Dinosphere. Come watch as we reveal one of Earth’s most fearsome predators, layer by layer.”

And based on Purdue Veterinary Medicine’s opportunity to “scan” the future exhibit, it’s sure to be stunning!