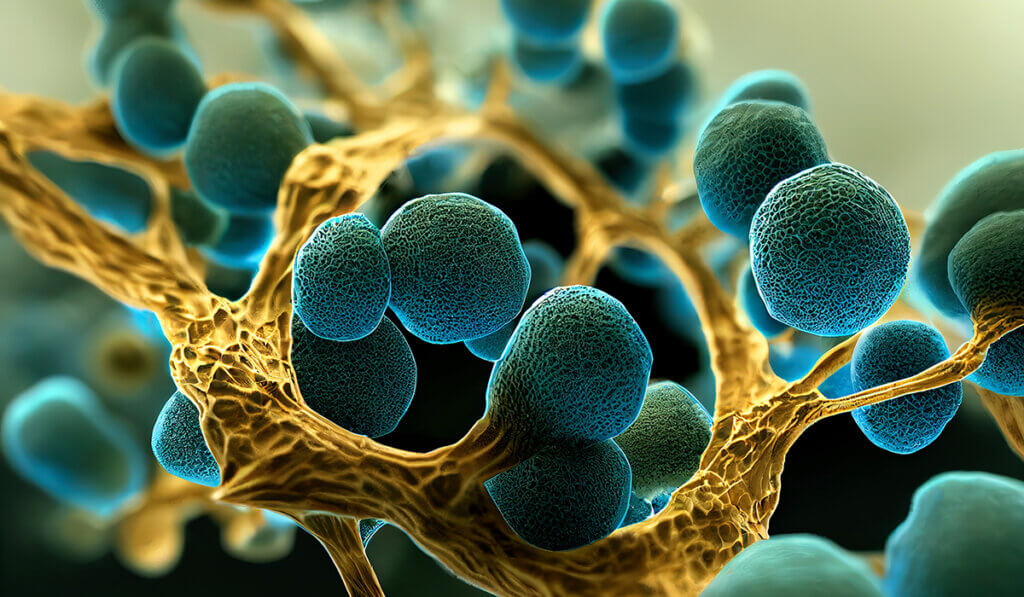

A new $2.4 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) will fund research led by a faculty member in the College of Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Comparative Pathobiology aimed at shedding light on a significant new health threat that involves an emerging multi-drug-resistant fungal pathogen. Dr. Shankar Thangamani, assistant professor of microbiology, is studying Candida auris, which he says predominately causes skin infections and has been classified as an urgent threat by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Antibiotic Threats Report (2019).

Dr. Thangamani explains that C. auris is prevalent in some long-term care facilities and acute care settings, where it can spread from patient to patient resulting in outbreaks and systemic infections. Moreover, several isolates of C. auris exhibit resistance to all three major classes of FDA-approved antifungal drugs: azoles, polyenes, and echinocandins. “This poses a significant challenge to treat infections caused by this fungal pathogen,” Dr. Thangamani said.

Unlike other Candida species that colonize the intestine, C. auris efficiently colonizes the skin and contaminates the patient’s environment resulting in rapid nosocomial transmission (transmission that occurs in hospital or other health care settings) and outbreaks of systemic infections. “Individuals colonized with C. auris can have a high fungal burden on their skin which has been positively correlated with environmental contamination, transmission and outbreaks of systemic infections,” Dr. Thangamani said.

His lab utilizes mouse models to understand how C. auris causes skin infections. “This fungal pathogen stays in the skin for several months and enters into circulation in the blood, and that’s where the problem arises, especially with elderly people, immuno-compromised people, cancer patients, and people in long-term care facilities. They are highly susceptible.”

A particularly problematic feature of C. auris is that patients don’t see any signs or symptoms, such as lesions or wounds. But if their hand touches a surface, they can transmit this bug to that inanimate object, and studies show that even there, it can stay alive for two weeks or even longer. Then, nobody knows it is there, but if another person comes and touches that surface, that’s how it transmits, within a hospital and in long-term care facilities.

Dr. Thangamani has been researching Candida auris for the last six years. During that time, cases of infection caused by the fungus have been on the increase. “This is new, and emerging, especially post-COVID,” he explained. “For a decade, there was a very low level of cases. But now it’s everywhere, and the fungal infections and concern about them are rising significantly all over the world. Last year, the World Health Organization (WHO) released a list of fungal priority pathogens that includes C. auris, which is ranked in the critical top priority group.”

The problem is compounded by the fact that not many drugs are effective in treating the resulting infections, which can be deadly. His research team is using mouse models to assess how the fungus causes infections and disease. “We are interested in how it infects mice and also humans because if you understand how it’s causing the infection, then you would have insight into what might be a way to treat it. That’s a long-term goal,” Dr. Thangamani said.

Understanding how skin factors such as microbiota and the immune system regulate C. auris colonization is necessary to be able to discern the emerging fungal pathogen’s basic biology and pathogenesis. This research is vital to identifying and developing novel strategies to prevent and treat this fungal pathogen in humans.

Dr. Thangamani is collaborating on the research with Dr. Elizabeth Parkinson, Purdue assistant professor of chemistry and Dr. Harm HogenEsch, Purdue Veterinary Medicine associate dean for research and Distinguished Professor of Immunopathology, as well as Dr. Douglas Bernstein, associate professor of biology at Ball State University. “We have a strong team that impressed the grant reviewers,” Dr. Thangamani said.

News of the grant also was important to Dr. Thangamani’s graduate student researchers. “We all were super excited when we first learned our lab had been awarded such a prestigious grant,” said PhD student Garrett Bryak. “I think it really inspires confidence on the part of our team that the work we are doing is truly important and that we are being recognized for our potential to contribute much-needed information to the scientific community.”

Another lab member, Dr. Kristine Towns, a veterinarian who is working on the research project in conjunction with her Laboratory Animal Medicine Residency, echoed Bryak’s thoughts. “I am so happy to contribute to the growth of an area that can benefit the health of the human population,” said Dr. Towns, who earned her DVM degree at Purdue. “I am very excited to contribute to the growth in knowledge about how this fungus can infect people. It is a globally important disease and little is known about the pathogenesis.”

Dr. Towns just recently joined Dr. Thangamani’s lab, and said she is not at all surprised he succeeded in obtaining this grant. “Dr. Thangamani is consistently working hard on grant funding and finding ways to have his students excel in this area of research,” Dr. Towns said. “I do feel that it is a wonderful opportunity for Dr. Thangamani to grow his lab and research, as he has a drive to grow knowledge in this area.”

She also commends Dr. Thangamani for being a great mentor to his students. “He expects hard work, drives timelines, fosters independent thinking, and in turn develops good scientists,” Dr. Towns said. “Given that I enjoy research, this experience is influencing my consideration of a career in academia.”