PVM Cancer Researcher Collaborates on Creating Device to Identify Risks for Breast Cancer

Make a Gift

Support the College

Dr. Sophie Lelièvre, professor of cancer pharmacology in the Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine.

Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine Professor of Cancer Pharmacology Sophie Lelièvre is moving mountains with her contributions to breast cancer research.

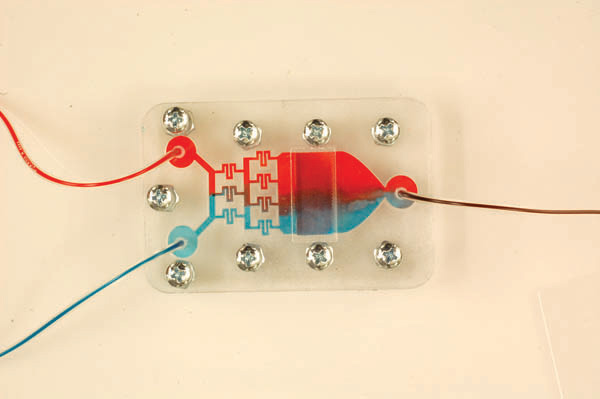

Dr. Lelièvre, a faculty member in the College’s Department of Basic Medical Sciences, heads up research concerning nutritional effects on breast cell biology and now is working on a project to create a device that could help identify risk factors that cause breast cancer. Called “risk-on-a-chip”, the device itself is a small plastic case with several thin layers and an opening for a piece of paper where researchers can place a portion of tissue. This tiny environment produces risk factors for cancer and mimics what happens in a living organism.

Dr. Lelièvre puts an emphasis on the importance of the most critical window of time for breast cancer prevention: before birth leading all the way up to puberty. “We want to be able to understand how cancer starts so that we can prevent it,” she said.

Cancer is a disease of gene expression, and organization of genes is specific to a particular species and organ, which means it wouldn’t be useful to perform this study on rats or mice. Thus, Dr. Lelièvre needs a model that will mimic the organ in question. She teamed up with Dr. Babak Ziaie, professor of electrical and computer engineering at Purdue, to create the device.

“Unlike conventional 2-D monolayer cell culture platforms, ours provides a 3-D cell culture environment with engineered gradient generators that promote the biological relevance of the environment to real tissue in the body,” said Rahim Rahimi, a graduate student in Dr. Ziaie’s lab.

Demonstration of concentration gradient in microfluidic system using red and blue color dye solutions.

The risk-on-a-chip is based on an earlier cell culture device developed by Drs. Lelièvre and Ziaie to study cancer progression. To modify it for prevention, Dr. Ziaie plans to add nanosensors that measure two risk factors: oxidative stress and tissue stiffness.

Oxidative stress involves a chemical reaction that occurs as the result of diet, alcohol consumption, smoking, or other stressors, and it alters the genome of the breast, aiding cancer development. The risk-on-a-chip will simulate oxidative stress by producing those molecules in a cell culture system that mimics the breast ducts where cancer starts.

Tissue stiffness refers to the stiffness of breast tissue, which has been found to contribute to onset and progression of breast cancer. The research team will measure stiffness within a tunable matrix made of fibers, whose density is relative to stiffness.

Breast cancer is particularly difficult to prevent because multiple risk factors work independently or in combination to promote disease onset. To account for this, the risk-on-a-chip will be tailorable to different groups of women at-risk.

“We need to see if there’s a difference in primary cells from Black women or Asian women or White women, because that matters,” Dr. Lelièvre said. “The way our genome is organized depends on an individual’s ancestry and lifestyle; it’s very complex. That’s why cancer is so difficult to treat.”

The research team believes the risk-on-a-chip could be used to study additional risks by adding more cell types and biosensors. They estimate that optimization for each new condition will take between six months and a year.

Drs. Lelièvre and Ziaie have received a joint grant from the Department of Defense to create and test the device with structures that mimic the mammary gland. The grant will provide more than $500,000 over the next two years.

This project is part of the International Breast Cancer and Nutrition collaboration (IBCN), which involves a group of multidisciplinary research teams that seek to elucidate the common link between nutrition and breast cancer. Launched at Purdue University, IBCN is the first dedicated worldwide effort in exploring the links between diet, the genome, and the risk of breast cancer.

Writer(s): Purdue Veterinary Medicine News | pvmnews@purdue.edu