Purdue Research Spearheaded by Dr. Riyi Shi Could Help Lead to Proper Treatments Against Long-term Effects Soon After Head Trauma

How much time elapses between a blow to the head and the start of damage associated with Alzheimer’s disease?

A device that makes it possible to track the effects of concussive force on a functioning cluster of brain cells suggests the answer is in hours. The “traumatic brain injury (TBI) on a chip” being developed at Purdue University opens a window into a cause and effect that announces itself with the passage of decades but is exceedingly difficult to trace back to its origins.

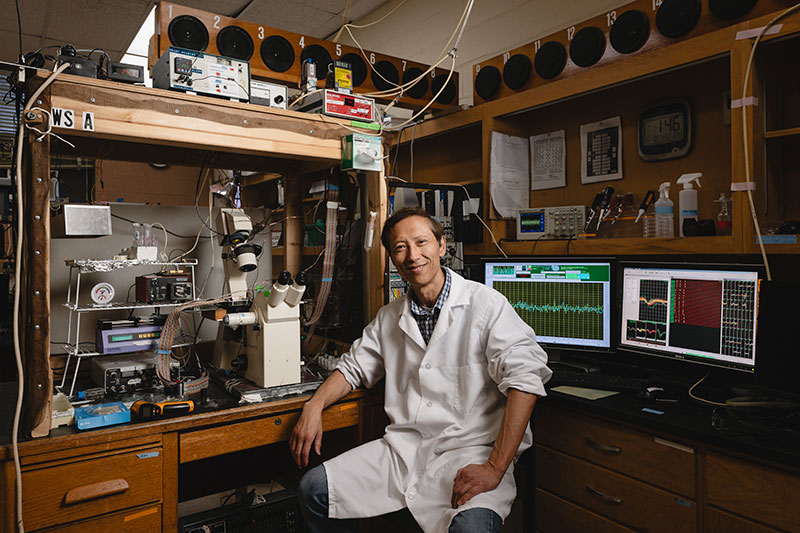

“We’re basically creating a miniature brain that we can hit and then study,” said Dr. Riyi Shi, lead researcher and the Mari Hulman George Endowed Professor of Applied Neuroscience in Purdue University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. “We know there’s a link between TBI and Alzheimer’s; that’s well established in clinical observation. But teasing out the basic essential pathway is not easy. With the TBI on a chip, we’re able to test a lot of hypotheses that would be very difficult to do in living animals.”

In a study recently published in Lab on a Chip, a research team led by Dr. Shi subjected functioning clusters of cultured neurons from embryonic mice to three blows of 200 g-force, each approximating the higher end of what a football player receives in a single hit. The trauma leads to an immediate surge in production of acrolein — a molecule associated with oxidative stress and neurodegenerative disease — and a rise in misfolded clumps of the protein amyloid beta 42 (AB42), which is found in masses called plaques in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Additional experiments traced the links among impact, acrolein, and AB42.

The TBI on a chip device can also be used to test possible therapeutics, including drugs known to reduce acrolein levels. In the current study, Dr. Shi’s research team used the device to show that the drug hydralazine, a known acrolein scavenger that is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for lowering blood pressure, reduces the amount of acrolein and levels of misfolded AB42 produced in the cluster of neurons after a hit. Dr. Shi, who has a long history of studying neurodegenerative disease, acrolein, and hydralazine, said the TBI on a chip enabled a finding he’s sought over two decades of study.

“Now that we know what’s happening, is there something we can do about it? And the answer is yes,” said Dr. Shi, a faculty member in the college’s Department of Basic Medical Sciences who also is a member of the Purdue Institute for Integrative Neuroscience and the director of the Purdue Center for Paralysis Research. “Acrolein is time-dependent; the longer it’s there, the more AB42 aggregation it will cause. Here we show that if we lower acrolein with this drug, we can lower inflammation and AB42 aggregation.”

The device, custom-fabricated at the Center for Paralysis Research, uses a pendulum to deliver a specific g-force to a small chamber housing a cluster of a quarter million neurons supported by a bed of nutrients. A microelectronic array embedded in the chamber measures the electrical activity of the neurons, which will sustain functional firing patterns for several weeks, while a clear viewing port allows microscopic observation of the neurons. Researchers remove the cluster of neurons from the chamber at intervals to take specific biochemical measurements.

“There’s several unique things that we do here, but one of the biggest is that you can hit this chip without damaging it, so you can give an impact to a live model and continue to study it,” Dr. Shi said.

Dr. Shi began working on the device in graduate school, incorporating over the course of several decades features that make it possible to study the aftereffects of an initial blow. A 2022 paper in Nature Scientific Reports used the device to show the surge in acrolein that occurs after a hit, and Dr. Shi said the most recent findings hint at the power of the model.

“Thanks to this device, people should know that when you get a concussion, you don’t have 10 years before you will see damage,” Dr. Shi said. “The clock starts ticking immediately, and if we want to do something about it, we need to act quickly.”

Within the first 24 hours after a hit, results show elevated levels of acrolein in the neuron clusters and a 350% increase in production of misfolded AB42. Dr. Shi said acrolein deforms normal AB42 by binding to sections of the protein that contribute to structural stability. Indeed, when the team conducted a simple experiment by combining large amounts of acrolein with normal purified AB42 suspended in fluid, they found elevated levels of misfolded AB42. The properly folded protein is sufficiently fragile that even subjecting normal purified AB42 in fluid (without acrolein) to an impact was enough to provoke misfolding.

“This amyloid beta pathology started within hours, maybe immediately. That’s never been heard of,” Dr. Shi said. “It’s like attacking the weight-bearing stud in a house wall. If you break that stud, of course the house is going to fall down.”

Dr. Shi was joined in the research by Purdue colleagues Edmond A. Rogers, first author, and co-authors Timothy Beauclair, Jhon Martinez, Shatha J. Mufti, David Kim, Siyuan Sun, Rachel L. Stingel, Nikita Krishnan, and Jennifer Crodian, senior research associate at Purdue’s Center for Paralysis Research, as well as Dr. Alexandra M. Dieterly, of Charles River Laboratories. The study was supported by the state of Indiana, the National Institutes of Health, and Plexon, Inc.

Moving forward, Dr. Shi said he may be able to incorporate multiple additional features, which would allow the measurements of minute forces that cells experience during the blow, and biochemical testing — like checking levels of acrolein — without removing cells from the chamber. Industry partners interested in further developing or commercializing Dr. Shi’s innovation should contact Joseph Kasper, of the Purdue Innovates Office of Technology Commercialization, at jrkasper@prf.org.