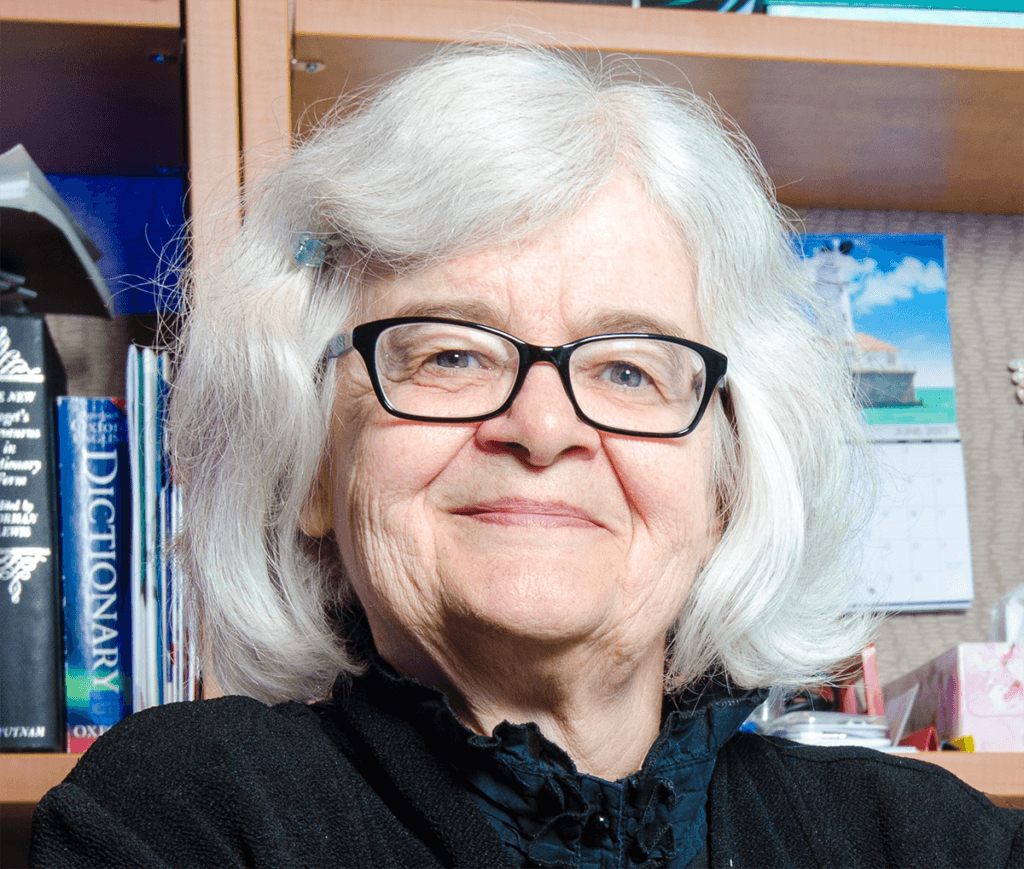

With issues related to COVID-19 vaccines continuing to dominate news headlines, the 2021 Coppoc One Health Lecture provided enlightenment on the topic for more than 80 attendees who watched a virtual presentation by Dr. Noni MacDonald, professor of pediatrics and former Dean of Medicine at Dalhousie University and the IWK Health Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia. An infectious disease specialist and vaccinologist, Dr. MacDonald is a passionate global health advocate and the first woman in Canada to have become a Dean of Medicine.

Hosted by the Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine, the annual campus-wide Coppoc One Health Lecture, which is free and open to the public, focuses on the symbiotic relationship between veterinary and human medicine and its world-wide impact. In her talk on November 4, Dr. MacDonald described how vaccine hesitancy in both routine and COVID-19 immunizations is a growing problem that will need to be addressed over the next decade and beyond. She said that a multitude of factors influence rates of vaccine hesitancy in a variety of manners and contexts. Looking deeper into these contexts and factors can provide insight into how the problem can be addressed in a tailored approach.

Dr. MacDonald emphasized that using evidence to develop strategies for overcoming vaccine hesitancy is the way forward into a future of high vaccine acceptance. Strategies to emphasize include addressing subgroups, utilizing the influence of health care workers, using effective discussion techniques, addressing pain and fear, making vaccine access easier, managing misinformation, and speaking up to peers.

The following summary recaps several of the issues that Dr. MacDonald addressed.

Vaccine Hesitancy

Vaccine hesitancy is the delayed acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability. Rates and severity of hesitancy is widely varied and influenced by a number of factors. Hesitancy exists on a spectrum ranging from complete acceptance to complete refusal. Not all individuals who choose to be vaccinated do so without questions or concerns. In high income countries, about 10-20% of the population is expected to be hesitant about some or all vaccines. Meanwhile only 1-2% will be truly anti-vaccination and fall on the complete refusal end of the spectrum. These rates of hesitancy vary across time, location, and vaccine.

In response to vaccine hesitancy and challenges presented by COVID-19, the World Health Organization and the World Health Assembly endorsed the Immunization Agenda 2030. This strategic plan for equity in immunization emphasizes the importance of leaving no one behind to extend the benefits of vaccines worldwide. Over the next decade, this plan will be implemented to increase vaccine access globally and reduce vaccine hesitancy through people-focused, country-owned, partnership-based, and data-enabled strategies.

“Even pre-COVID, the World Health Organization said that vaccine hesitancy was among the ten threats to global health. This is a big deal,” said Dr. MacDonald.

Contextual Factors

One thing that must be addressed in any attempt to reduce vaccine hesitancy is that the individual decision to be vaccinated or not is complex and context-specific. People also have certain tendencies and instincts when it comes to information that can either be damaging or can be used to the advantage of vaccine acceptance programs. First, people pay more attention to negative information than positive. People also tend to rely on anecdotal evidence over empirical data. When people hear a story about someone they know who had a bad experience with a vaccine, it sticks with them. That impact is not easily overwritten with spreadsheets and statistics.

The factors that contribute to hesitancy have been broken down and categorized in many ways. As Dr. MacDonald said, “There have been a number of models that have been developed to talk about the many, many, many factors that influence your decision to get a vaccine.” One model, known as the “Five Cs,” suggests that the primary barriers to vaccine acceptance are as follows:

- Complacency

When the perceived risk is low and other priorities are placed higher, people are less likely to act on getting vaccinated. - Confidence

People must feel that they can trust the vaccine, its delivery, and the policy makers who require them. - Constraints

Structural: low availability or high costs can be a major barrier to vaccination.

Psychological: appeal, acceptance, social norms, and other internal psychological factors have a great effect on hesitancy. - Calculation

The amount of time an individual commits to extensive information gathering can determine their acceptance of a vaccine. - Collective Response

The willingness to protect others goes a long way when it comes to vaccine acceptance. People who wish to protect those around them are much more likely to be vaccinated than those who are only concerned with themselves.

Dr. MacDonald also said that beyond the Five Cs model, other factors that influence vaccine hesitancy include politics and health care workers. She noted, when health care workers are vaccinated themselves and recommend immunizations, their patients are much more likely to also get vaccinated.

Evidence-Based Strategies

Dr. MacDonald said, with such a wide range of influences and varying degrees of vaccine hesitancy, it is important to look at strategies to combat hesitancy which are founded on evidence and efficacy. Many such strategies exist with ample research to support the techniques.

Detect and Address Subgroups with Lower Uptake

Certain groups of people will be more or less receptive to certain vaccines for many of the reasons previously discussed. When addressing these groups, taking that specific context into consideration is vital. Dr. MacDonald noted that not all people in these groups are strictly anti-vaccination and they should not be considered or treated as such. In order to address these different groups, data is needed. Coverage data can show how many people are not vaccinated or under-vaccinated, and where pockets of these individuals live. Program data shows the efficacy of the vaccine distribution. Behavioral and social data reveals barriers to vaccine uptake among certain groups.

Utilize Health Care Workers

The recommendation of a vaccine by a health care worker is extremely influential in the decision to accept vaccines. “Educating health care workers about vaccines and the strategies that work can very much increase a vaccine’s uptake,” said Dr. MacDonald.

Use Effective Discussion Techniques

Poorly delivered messages do not have as great of an impact as messages that are delivered well. Even when the content is accurate and sound, if the presentation fails to convey that, the communication will be ineffective. It is also important to remember that high acceptance rates do not indicate that there are no concerns regarding a vaccine. These concerns need to be addressed in well-constructed messages to increase confidence in vaccination.

Address Pain

Something often overlooked when attempting to increase vaccine acceptance is the factor of pain and needles. Dr. MacDonald said at least 10-15% of adults fear needles or the pain inflicted by receiving shots. Others have a much more severe phobia, which can be completely debilitating when it comes to getting immunized. Finding ways to reduce the pain and associated fear of vaccines is an important step to reducing hesitancy among these individuals. Decreasing pain will also decrease immunization stress-related responses such as fainting, headache, fatigue, and nausea which often serve to reinforce fears and anxiety about vaccines.

Make Access Easy

Dr. MacDonald pointed out that studies have shown that when an immunization is provided through a school, acceptance rates are significantly higher than when the same vaccination is offered through a doctor’s office. The access is made easy for parents who don’t have to coordinate getting their child out of school and to the doctor’s office. For the students, acceptance rates are high because it becomes a social norm. Other ways to improve ease of access include bundling vaccines, and having more vaccine sites, especially in rural or low income areas, with extended hours. Meeting the needs of disabled individuals and ensuring privacy for people also are important factors.

Manage Misinformation

Dr. MacDonald emphasized that there is a vast array of misinformation and it has been proven that such misinformation reduces vaccine acceptance significantly. Being aware of strategies and techniques used to spread misinformation can help people identify when they are being misinformed. It also is important to disprove and correct misinformation when it arises.

Speak Up

Dr. MacDonald concluded her presentation by emphasizing the importance of people speaking up to share accurate information. She explained that fear is powerfully persuasive and silence is easily misconstrued as support. Providing information to address the concerns of peers can make a big difference. Dr. MacDonald observed that it’s okay to agree to disagree with someone who won’t trust the information you give them. But, she said it is crucial to point out that there is no debate in science regarding the importance of immunization.

About the Coppoc One Health Lecture

Established in 2014, the Coppoc One Health Lecture Series is named in honor of Dr. Gordon Coppoc, Purdue professor emeritus of veterinary pharmacology, and his wife, Harriet. Dr. Coppoc is the former head of Purdue Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Basic Medical Sciences. He also served as director of the Indiana University School of Medicine-Lafayette and associate dean of the Indiana University School of Medicine before retiring in 2014.