Indiana State Board of Animal Health Veterinary Advisory

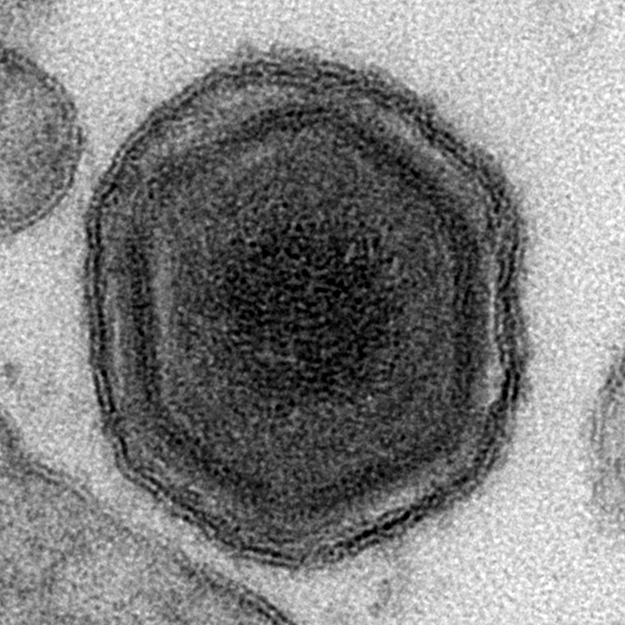

Africa Swine Fever Virus

Photo from the Institute for Animal Health

African Swine Fever

The growing number of diagnosed cases of African swine fever (ASF) throughout China is raising concern. The Indiana State Board of Animal Health (BOAH) is working with Indiana Pork to increase producer awareness of clinical signs and remind producers to contact a private practitioner with concerns.

Clinical Signs

African swine fever can present in a peracute, acute, subacute or chronic manifestation. Severe cases that affect large numbers of animals may be readily recognized; however, some herds develop milder clinical signs that are easily confused with other diseases such as salmonellosis, PRRS, or erysipelas.

Sudden deaths with few lesions (peracute cases) may be the first sign of an infection in a herd. Acute cases are characterized by a high fever, anorexia, lethargy, weakness and recumbency. Erythema can be seen, and is most apparent in white pigs. Some pigs develop cyanotic skin blotching, especially on the ears, tail, or legs. Pigs may also have diarrhea, constipation and/or signs of abdominal pain; the diarrhea is initially mucoid and may later become bloody. Pigs may also have visible signs of hemorrhagic tendencies, including epistaxis and hemorrhages in the skin. Respiratory signs, nasal and conjunctival discharges, and neurological signs have also been reported. Pregnant animals frequently abort; in some cases, abortions may be the first signs of disease. Death often occurs within 7 days to 10 days.

Subacute or chronic cases of African swine fever, caused by moderately virulent isolates, is similar to acute ASF but with less-severe clinical signs. Affected pigs usually die or may recover and carry and shed virus for several months.

Post Mortem Lesions

On gross necropsy, lesions are hemorrhagic in nature and occur most consistently in the spleen, lymph nodes, kidneys, and heart. The spleen is often enlarged and may be dark red to black and friable. The lymph nodes are often swollen and hemorrhagic, and may look like blood clots; the nodes most often affected are the gastrohepatic and renal lymph nodes. Petechiae are common on the cortical and cut surfaces of the kidneys, and sometimes in the renal pelvis. Hemorrhages, petechiae and/or ecchymoses are sometimes detected in other organs including the urinary bladder, lungs, stomach and intestines. Pulmonary edema and congestion can be prominent in some pigs. There may also be congestion of the liver and edema in the wall of the gall bladder and bile duct, and the pleural, pericardial and/or peritoneal cavities may contain straw-colored or blood-stained fluid.

(Photos may be viewed at: https://bit.ly/2NtiWoc )

Transmission of ASF

The African swine fever virus is easily spread between pigs by direct contact or indirectly from contact with contaminated objects. The virus can survive in the environment, on shoes and clothing, as well as vehicles, and in feed components. Uncooked or undercooked meat (including refrigerated and frozen products) can carry the virus, making garbage feeding and smuggled food items threats. Ticks, flies, and other insects may also spread the virus. Currently no commercial vaccine is available for ASF. (NOTE: The virus does not pose a threat to human health or food safety.)

Suspicious Cases and Diagnostic Testing

ASF is a foreign animal disease (FAD). Suspicious cases—particularly when higher-than-normal mortality is evident—should be reported to BOAH. As part of the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN), the Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (ADDL) at Purdue is approved to run an initial PCR on whole blood when warranted; however, testing for ASF can only be completed as part of a FAD investigation. Veterinary practitioners must contact BOAH to initiate an investigation and facilitate authorization of sample submission. Utilizing Purdue ADDL will provide the fastest reporting of results to BOAH.

The diagnostic specimen of choice for ASF is whole blood collected in purple-top tubes. In addition to whole blood, other tissue samples such as spleen, lymph nodes, and tonsil may be submitted as part of the FAD investigation.

Practical Preparedness Now

Producers and veterinarians can take steps NOW to be ready should an FAD event happen. BOAH has launched a webpage (www.in.gov/boah/2857.htm) that outlines essential steps to be prepared.

Producers should:

- Register the farm/business for a DUNS number and the SAM system

- Obtain a premises identification number (premises ID) for each location where swine are located

- Contact BOAH to ensure each premises ID number is matched to each location of swine for a production system

Veterinarians need to:

- Use barcode numbers on laboratory samples; these can be printed via https://lms.pork.org/Premises/ using the premises ID for the site where the samples were collected

- Use electronic certificates of veterinary inspection for all movements (or a Commuter Herd Agreement)

Biosecurity and Preventing ASF

Maintaining a high level of on-farm biosecurity is the best protection. In addition to using a disinfectant specifically labeled for ASF, producers should know:

- Those who host international visitors or travel abroad should pro-actively follow guidelines (https://www.pork.org/production/animal-disease/foreign-animal-disease-resources/).

- Many feed components are sourced from overseas. Research has shown that ASF virus particles can survive in certain feed ingredients for an extended period of time. Some producers may choose to hold feed for a period of time to reduce risk. Research is currently underway to determine if this could be an effective biosecurity measure; however, study results are not expected for a few months. (http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0194509 )

More About ASF

More information about ASF and the situation in China is online at: www.pork.org/production/animal-disease/foreign-animal-disease-resources/

Anyone interested in receiving email and/or text updates about securing Indiana’s pork industry and updates about how the ongoing ASF situation is affecting the state can subscribe online at the red link at the top of the page at: www.in.gov/boah/2857.htm

By using our website you agree to our

By using our website you agree to our