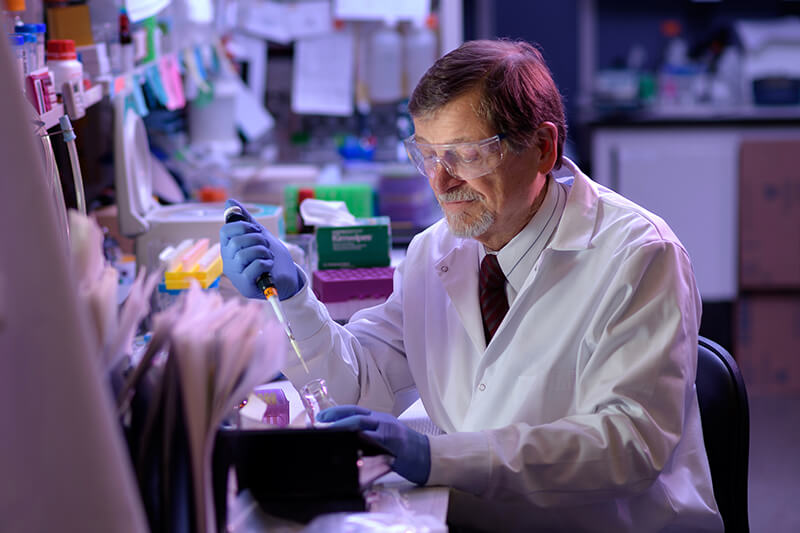

A new approach to cancer immunotherapy has the potential to be a universal treatment for solid tumors, according to researchers at Purdue University, including a Distinguished Professor in Purdue Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Comparative Pathobiology. The research was led by Dr. Philip Low, Purdue’s Presidential Scholar for Drug Discovery and Ralph C. Corley Distinguished Professor of Chemistry, and Dr. Timothy Ratliff, Distinguished Professor of Comparative Pathobiology and the Robert Wallace Miller Director of the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research.

The two scientists collaborated to develop and test the new treatment that works not by attacking the cancer cells themselves, but by focusing on immune system cells that, ironically, feed the tumor and block other immune system cells from destroying it. The first details of the approach were published recently in the journal Cancer Research.

Dr. Low said the treatment is “totally unique” and has been shown to work in six different tumor types. So far, the treatment has been tested in human tumor cells in the laboratory and in human tumors in animal models. The approach targets immune cells that, in cancerous tumors, stop the body’s own defenses from killing the tumor. “We can reprogram the immune cells within the tumor to help kill the tumor instead of allowing these cells to help the tumor grow,” Dr. Low said.

In this technique, an anti-cancer drug that would normally be too toxic for human use is linked to folate, which is a type of vitamin B. Almost no normal cells have a receptor for the folate, so it passes on through the body, but certain cancer-associated immune cells do.

“We use the vitamin folate to target attached drugs specifically to these nonmalignant cells within a tumor mass that, unfortunately, promote tumor growth. These tumor-associated macrophages love folate,” Dr. Low said. “They have an enormous appetite for it. They take it up right away, and if they don’t, the compound passes in the urine within about 30 minutes. So, we ‘re using folate as a kind of Trojan horse to trick the tumor-promoting immune cells into eating a drug that will reprogram them into tumor-fighting immune cells.”

Dr. Ratliff explained that this treatment may prove to be more universally effective than current cancer immunotherapies. “There are therapeutic antibodies that are used on some types of cancer. And many people have heard of checkpoint immunotherapies, which block certain parts of the immune response,” Dr. Ratliff said. “When I talk to groups, I always point out that former President Jimmy Carter had metastatic brain cancer, and he went through immunotherapy, and it eliminated the cancer for him.”

“But the problem is,” Dr. Ratliff continued, “that only about 20 percent of the patients actually respond. So, we need to take a different approach to modulating the immune response.” Dr. Ratliff said the folate-targeted approach is exciting because it is the first research project that has found a way to target the cells that boost tumor growth in the tumor environment.

“These are cells that are important to the tumors, but they aren’t the tumor cells themselves,” Dr. Ratliff said. “By targeting these myeloid cells within the tumor, we have a universal process because these cells are present in all of the solid tumors.”

Dr. Low said the new immunotherapy treatment could be available to patients within a decade. “On average, this usually takes ten years, but we have a small team and we’re aggressive. So, I think there’s a reasonable chance this could make it to the public within seven years or something like that,” he said. “It would probably cost a couple hundred million dollars, at the very least, to develop and test this drug.”

“So it’s not going to be cheap, and it’s not going to be easy. But this drug has enormous potential to save many lives. So, we will do our best.”

Click here to view a complete news release about the research.